Ophthalmology Specialty & Cataract Surgery Training

Ophthalmologists are physicians specializing in the comprehensive medical and surgical care of the eyes and vision.

Ophthalmologists are the only practitioners medically trained to diagnose and treat all eye and visual problems including vision services (glasses and contacts) and provide treatment and prevention of medical disorders of the eye including surgery.

Ophthalmology is an exciting surgical specialty that encompasses many different subspecialties, including: strabismus/pediatric ophthalmology, glaucoma, neuro-ophthalmology, retina/uveitis, anterior segment/cornea, oculoplastics/orbit, and ocular oncology.

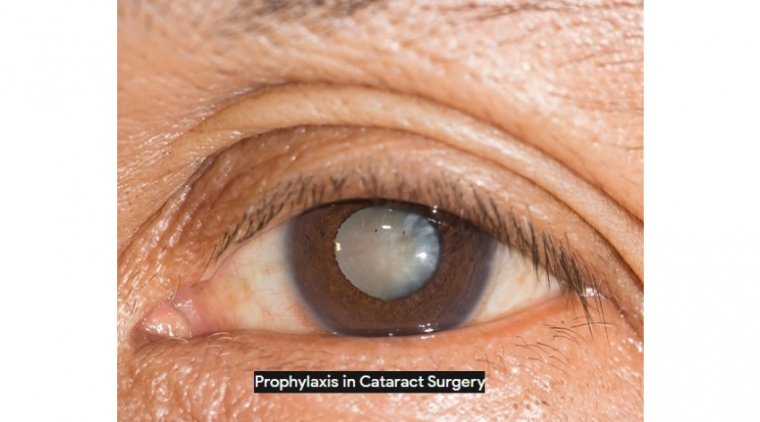

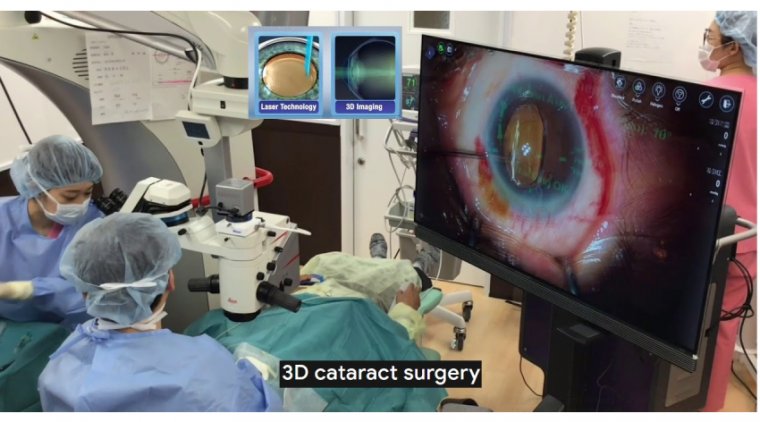

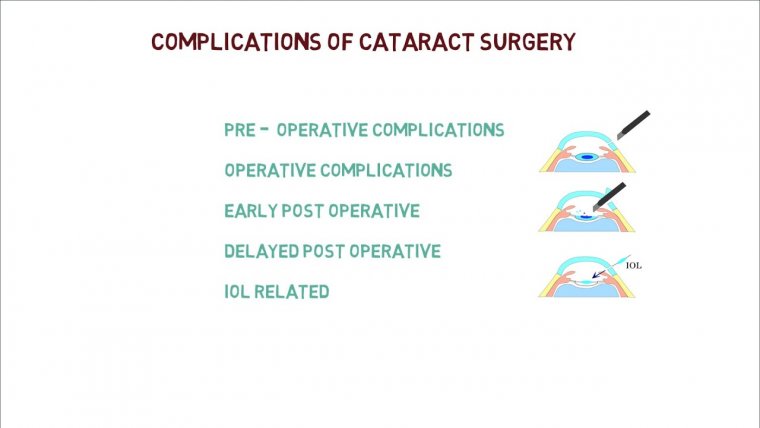

Cataract surgery and basic glaucoma surgery are two of the more common procedures an ophthalmologist routinely performs that requires such skill.

During the first year, residents learn to do different parts of cataract surgery and go through the EyeSi training simulator curriculum during their VA rotation.

In second year, the residents complete the EyeSi training simulator curriculum and begin to do full cataract surgery cases, performing all parts of the surgery.

In the chief year, residents have a cataract surgery boot camp with lectures and practice sessions in July-September, and continue to expand their surgical repertoire and practice more complicated techniques such as sutured IOL placement and extra capsular cataract extraction.

In addition to ad hoc sessions with ready access to surgical instruments, Kitaro eyes, pig eyes, and human cadaver eyes; Residents in each clinical year structures wet labs for practicing phaco-emulsification and anterior segment techniques with the latest equipment focusing on phacoemulsification basics, advanced cataract microsurgery (iris hooks, Malyugin ring, i-ring, miLoop, capsular tension rings, and sutured intraocular lenses), and manual small incision cataract surgery.

There are also numerous subspecialty wetlabs organized every year for all the residents to attend, including:

· drills session for orbital fracture repair with the oculoplastics service

· fillers and botulinum toxin sessions

· Glaucoma surgical procedures wet lab (MIGS iStent, glaucoma tube shunt, trabeculectomy, endocyclophotocoagulation)

· Corneal suturing, penetrating keratoplasty, and other anterior segment procedures

Strabismus/pediatric ophthalmology deals with eye diseases in children, involving all intraocular surgery as well as strabismus (crossed eyes) surgery, which incorporate detailed eye muscle surgery.

Neuro-ophthalmology deals with the eye as it relates to neurological disease. It is a complex and intricate subspecialty that requires knowledge of the visual pathways, eye-movement patterns, optic nerve disease, and systemic neurological diseases with visual manifestations.

Retina/uveitis concentrates on diseases, often systemic or inflammatory, involving the retina and vitreous (posterior aspect of the eye).

This includes surgical and laser treatment of diseases such as retinal detachments, diabetic retinopathy, and others. It also requires proficiency of challenging microsurgical techniques.

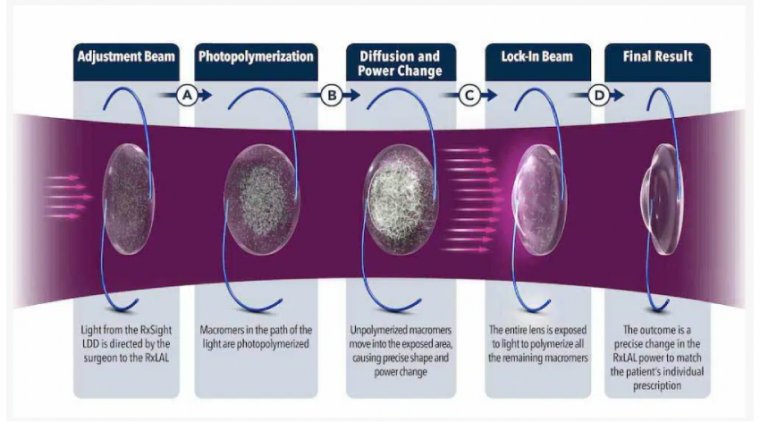

In addition to routine cataract surgery, cornea/anterior segment specialists are skilled in corneal transplantation and one of the most exciting areas of medicine, refractive eye surgery (vision correction).

A final subspecialty field of ophthalmology is ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. This fellowship encompasses aesthetic, plastic and reconstructive surgery of the face, orbit, eyelids, and lacrimal system.

This includes learning techniques to remove tumors in the orbit, and on the surface of the eye, such as conjunctival melanoma, as well as repairing bony fractures of the periorbital area and face.

This surgical field allows you to care for patients of all ages, treat and identify systemic diseases, and perform some of the most challenging of surgical procedures ranging from microsurgery around and inside the eye to facial surgery involving reconstructive and aesthetic surgery.

To become a general ophthalmologist, the specialty requires four years of postgraduate specialty training after the completion of a medical degree (MD).

The Feelings of Ophthalmology Trainees

Ophthalmology trainees often feel they are being ‘thrown in at the deep end’ early on in their career.

Trainees are now expected to clearly demonstrate evidence of having acquired the expected knowledge, clinical, technical, and surgical skills at each stage of their training in order to progress.

Ophthalmology is one of the most competitive specialties to pursue training in worldwide. In the United Kingdom, the ST1 entry national selection competition ratio for the past few years has ranged between four to five applicants per post.

The specialty attracts a large number of applicants due to a variety of reasons including the work-life balance, the job security due to the increasing need for ophthalmology services, and the ever-evolving nature of the specialty particularly relating to technological advances such as newer devices and artificial intelligence that makes ophthalmology an exciting field to work in.

This popularity among medical graduates, however, has meant that applicants need to invest significant time and money to make their portfolios competitive as it forms a significant part of the selection process.

This article will provide insight into both the financial and non-financial costs associated with applying for ophthalmology specialty training, looking into detail at the specific sections of the portfolio.

Portfolio-Associated Costs

There are costs associated with building up a portfolio for application to ophthalmology training. From a financial perspective, the main expenses are associated with obtaining additional degrees, attending conferences, sitting examinations and publishing in journals.

While the cost can be subsidised through bursaries, awards and research grants, these are competitive and as one enters foundation training, they are rarely available.

However, junior doctors also have study budget available once qualified as an FY2 that can be utilised to attend educational courses and conferences.

One may argue that instead of paying large sums for international conferences and publishing in costly journals, individuals could instead attend local meetings and submit to journals that do not charge article processing fees.

While there are points and educational experiences to be gained from these, the former is often less than what could be obtained from attending or presenting at international meetings and publishing research in high impact peer-reviewed journals, many of which charge a publication fee.

This difference in points attainment is likely because having research accepted in a high-quality meeting or journal is reflective of the quality of research undertaken by individuals, hence rewarding candidates with greater points.

With regards to time commitment, various things on the portfolio such as publications, prizes and projects can often take years. Some are even time-limited, such as the inability to pursue intercalated degrees or sit the Duke Elder examination after finishing medical school.

Due to this, both an early interest in ophthalmology and awareness of the portfolio would be beneficial in planning how to achieve these prior to ophthalmology specialty training applications.

What is now a common practice among junior doctors is to undertake an FY3 year that can be used to build up the portfolio, including sitting the FRCOphth Part 1 examination, which otherwise may be difficult to study for during FY1 or FY2 due to ongoing work commitments but if passed can reward a candidate three points.

“It is unclear whether the costs involved in applying for specialty training have an impact on candidates choosing a particular training programme”

It is unclear whether the costs involved in applying for specialty training have an impact on candidates choosing a particular training programme.

A survey in 2016 found that foundation year doctors on average spent £1460 to undertake courses, conferences, postgraduate exams and qualifications for specialty training applications.

Those applying for surgical specialities invested £2535, which was significantly higher than the overall average. This is likely an underestimate given costs undertaken during medical school were not taken into account and the time commitment required was not considered.

Moreover, there will be significant variability for costs incurred among surgical specialties given the different entry requirements.

Hence further research is needed investigating the true costs undertaken to apply for speciality training and whether this impacts on individuals choosing particular specialties.

This will also help address the need for appropriate funding and study leave being made available to both medical students and junior doctors to invest in and build their portfolio.

Impact of COVID-19

With the COVID-19 pandemic, achieving points on the portfolio has been made both easier and more difficult in some ways.

Virtual conferences have given individuals the chance to present their research from the comfort of their home without incurring any travel costs.

However, recurrent lockdowns and social distancing requirements has led to various meetings and courses being cancelled or postponed.

From a recruitment point of view, the redeployment of teams within the NHS has also meant that some ophthalmology trainees may not been able to fully progress, thus resulting in reduced availability of posts and possible further increase in competition necessitating applicants to work even harder to obtain a training post.

However, the competition ratio for the 2021 recruitment cycle has yet to be published.

While there are number of associated costs with building up an ophthalmology specialty training portfolio that need consideration, these play an important role in the professional development and educational experience of future ophthalmologists.

Moreover, with ophthalmology being the rewarding career it is, the consistently high competition ratio is evidence that, despite the costs, candidates are willing to make any effort required to maximise their chances of securing a training number.