Management of Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage during Cataract Surgery

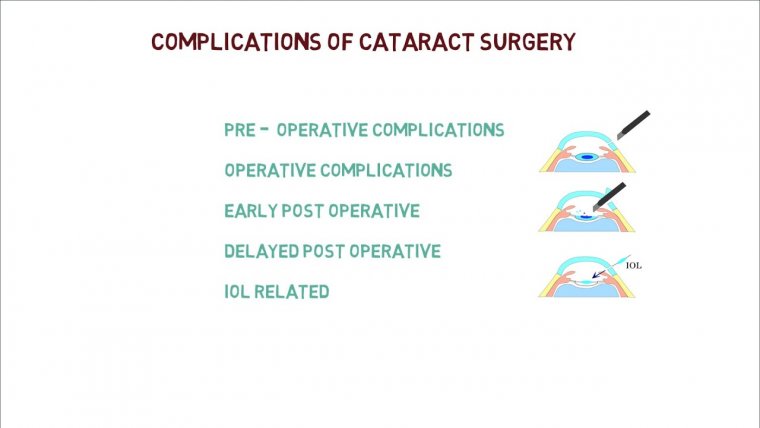

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SCH) is one of the most frightening and devastating complications of ophthalmic surgeries. It occurs as a result of rapid blood accumulation in the suprachoroidal space due to increased tension and rupture of the posterior ciliary arteries or vortex veins.

Acute expulsive SCH might occur during surgery, while a delayed SCH might take place hours or days after the surgery. SCH presents with severe eye pain, marked decrease in visual acuity, shallow anterior chamber, and severe increase in intraocular pressure (IOP).

Intraoperative SCH is thought to be a result of acute hypotonia or fluctuation of the IOP. Other reasons include choroidal vascular congestion (due to peribulbar or retrobulbar anesthesia) and atherosclerotic vasculature.

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SCH) is a rare, but potentially vision threatening pathology that may manifest as a consequence of intraocular surgery. It occurs when blood from the long or short ciliary arteries fills within the space between the choroid and the sclera.

Suprachoroidal hemorrhages are classified in several ways. They may be categorized with respect to size and the extent of hemorrhage, relationship to intraocular surgery (intraoperative/expulsive or postoperative/delayed), or precipitating events (spontaneous, blunt/penetrating trauma or perioperative).

SCH occurs less commonly in association with modern techniques of cataract surgery than with glaucoma, vitreoretinal, and penetrating keratoplasty (PK) procedures.

The extent of SCH ranges from localized, self-limiting hemorrhages to expulsion of intraocular contents. It is important to recognize this complication early and to manage it expediently.

The incidence of SCH during cataract surgery has decreased with the evolution of newer techniques.

These include the use of topical anesthesia instead of retrobulbar block and the adoption of smaller-incision surgery and self-sealing clear corneal incisions instead of ECCE, with its larger surgical wounds.

The estimated incidence of SCH during cataract surgery reported in the past 25 years is approximately 0.03% to 0.1%, compared with earlier reports of up to 0.8% with older techniques.

The majority (up to 50%) of cataract surgery–related SCH occurs during phacoemulsification or nuclear expression or after removal of the nucleus.

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SCH) is a rare but devastating complication associated with incisional intraocular surgery as well as trauma. Characterized as a sudden and rapid accumulation of blood within the suprachoroidal space, SCH can often result in severe, painful loss of vision.

It is believed that sudden intraocular pressure (IOP) fluctuation and/or hypotony cause the posterior long or short ciliary arteries to rupture, leading to the devastating bleed, although this is unclear.

Numerous risk factors for SCH have been well documented, including systemic factors, such as advanced age, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, or antiplatelets/anticoagulation medications.

Ocular risk factors leading to SCH development include high myopia, glaucoma, aphakia, pseudophakia, or previous intraocular surgery.

Intraoperatively, SCH can manifest as a complication of retrobulbar anesthesia, elevated IOP, Valsalva maneuvers (i.e., coughing, bucking, straining, etc.), hypertension, general anesthesia, and so on.

Postoperatively, hypotony and Valsalva maneuvers can trigger SCH. Although SCH is associated with various ocular procedures, including cataract surgery, glaucoma filtering procedures, keratoplasty, and vitreoretinal surgery, this article will focus more on phaco-related choroidal hemorrhages and their management, but the lessons herein can be applied to most SCH scenarios.

The incidence of SCH during or after cataract surgery is reported to range from 0.03% to 0.1% throughout the past 25 years, compared with 0.8%1 with older techniques.

SCH is diagnosed clinically by sudden signs of severe ocular pain, a looming shadow progressively darkening the red reflex, shallowing of the anterior chamber, decreased vision, elevated IOP, and a firm globe.

Poor prognostic factors include SCH encompassing most/all 360 degrees, extracapsular cataract surgery, posterior capsule rupture during phacoemulsification, retinal apposition (“kissing choroidals”), and retinal detachment.

As SCH remains a serious complication leading to significant visual loss, urgent diagnosis and management, including early detection, close monitoring of symptoms, and appropriate medical and/or surgical procedures, help maximize the chances of visual recovery.

In terms of treatment options, which will be discussed below, classic teaching advocates for surgical intervention in 1 to 2 weeks, as this is typically when liquefaction of the clotted hemorrhage occurs.

However, is surgery always necessary? The following two SCH cases illustrate great outcomes with conservative, nonoperative management.

CASE EXAMPLE 1

A 75-year-old male with hypertension and chronic naproxen use was seen in the retina clinic 2 days after undergoing complex phacoemulsification complicated by suprachoroidal hemorrhage OS near the end of the case.

The case was complicated by zonular instability needing a CTR-ring, posterior capsular rupture after IOL implantation, CTR and IOL explantation, anterior vitrectomy, and SCH occurring near the end of the case.

On presentation, the patient had left eye pain, hand motion visual acuity, and IOP in the 30s. The exam showed mild hyphema, aphakia, large non-kissing hemorrhagic choroidals, and flat, but corrugated, retina.

We counseled the patient as to the guarded visual prognosis, the need for intense medical therapy and frequent follow-ups, as well as the need to wait 1 to 2 weeks for the clotted hemorrhage to liquefy before pursuing surgery to drain the SCH.

We started him on topical atropine, max IOP-lowering drops, oral acetazolamide (Diamox Sequels, Teva Phamaceuticals USA), and topical and oral steroids.

Over time, we saw consistent improvement symptomatically and on exam, so we canceled surgery and continued following him closely while slowly tapering him off of the medications.

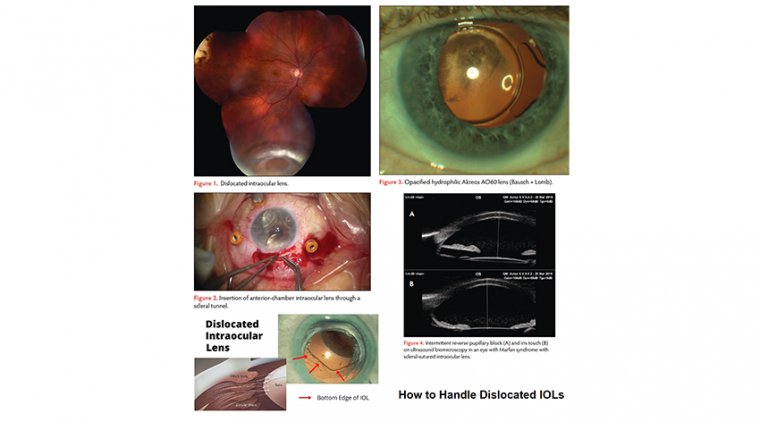

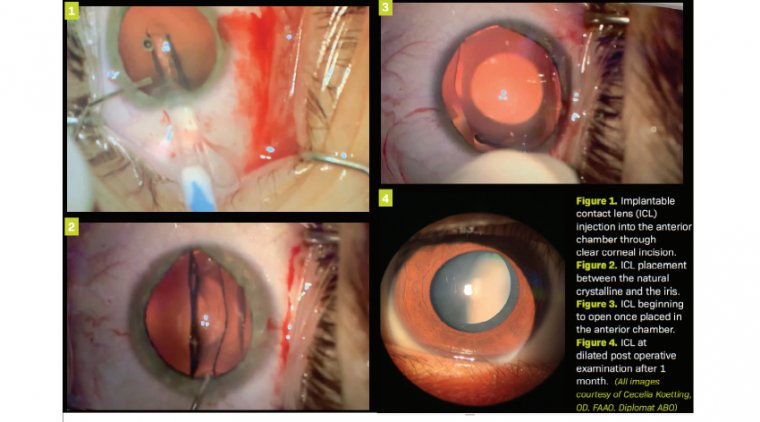

Once we deemed him stable enough for secondary IOL placement, an uneventful surgery took place to insert an anterior chamber intraocular lens around 9 months after presentation.

He was last seen around 1 year after presentation, and everything looked fantastic: He had a VAsc of 20/70 (PH 20/40) and IOP 14 in his left eye.

The retina was flat with peripheral pigmentary changes and rows of circumferential choroidal fold lines, and OCT showed a flat macula with mild ERM, ellipsoid zone changes, and improving choroidal folds.

CASE EXAMPLE 2

A 73-year-old female experienced an expulsive choroidal hemorrhage in her right eye during topical cataract surgery after having sudden, severe coughing during phacoemulsification.

A PC tear occurred, necessitating an anterior vitrectomy and sulcus IOL placement, at which point a suprachoroidal hemorrhage was noted. At clinic the same day, the patient noted significant eye pain alongside hand motion visual acuity and an IOP of 11.

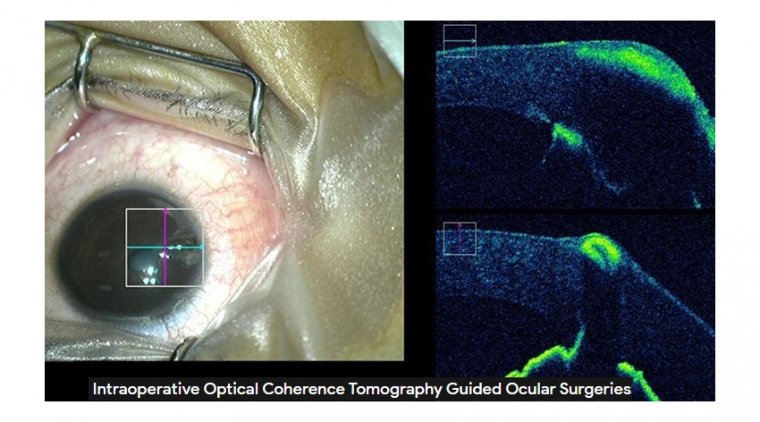

There were large hemorrhagic non-kissing choroidals, a vitreous hemorrhage, and a flat retina best appreciated by B scan.

Medical management similar to Case 1 was employed with close follow up. After 3 weeks of close monitoring and medical treatment, the patient reported improved vision with a VAsc of 20/50 (PH 20/30).

Four months after presentation, the patient was tapered off meds. Her clinical findings at that time: VAsc of 20/20, well-centered sulcus IOL, resolved vitreous hemorrhage and choroidal hemorrhages, and the retina remained flat.

DISCUSSION

Postoperative management of SCH traditionally necessitated surgical intervention consisting of choroidal drainage with or without pars plana vitrectomy.

Surgical management with various techniques has been reported to successfully restore vision in patients that could otherwise result in phthisis or severe loss of vision if left untreated.

However, the optimal time for surgical intervention post incidence has not yet been definitively set. Previous studies have found that the optimal time for surgical intervention may be around 10 to 14 days after SCH occurence.

This is due to the previous observation that drainage of an acute SCH creates an outflow that decreases the speed of thrombus liquefaction.

Additionally, posterior sclerotomy performed to evacuate blood in the suprachoroidal space and lower the IOP has proven to paradoxically result in a much larger choroidal hemorrhage resulting in vitreous hemorrhage, hyphema, and a worsening rise in IOP.

This is theorized by the observation that elevated IOP from SCH may provide a protective tamponading effect against further bleeding, which is lost when the hemorrhage is drained too quickly in the acute event window.

Thus, in most cases, drainage is indicated when the suprachoroidal clot has shown signs of liquefaction on B scan ultrasonography around the 2-week mark. However, not all SCHs may require surgical intervention.

Cases with vitreous hemorrhage, vitreous incarceration, kissing choroids, or retinal tears/detachments have been reported to generally require surgical treatment, while mild, non-appositional SCHs may be observed to resolve spontaneously.

Here we described 2 cases of intraoperative phaco-related SCH that were successfully managed medically without a need for surgical intervention.

Case 1 involved a hypertensive 75-year-old man on long-term NSAID-medication, while case 2 involved a 73-year-old woman who coughed significantly intraoperatively.

Both patients had severe non-kissing SCH with marked painful vision loss. Prompt medical management with topical and oral steroids, cycloplegics, IOP-lowering drops, and acetazolamide are necessary to begin as soon as possible.

It took patience and confidence to forego surgery and to continue to carefully monitor the slowly improving SCH cases.

Therefore, suprachoroidal hemorrhage cases, although rare, can be managed on a case-by-case basis in which medical treatment, patience, and time can sometimes prove sufficient without the traditional need for surgery after 2 weeks.

This conservative approach is an important option to consider, if the option is available, as surgical repair of SCH is often complex with a higher risk of complications.

While there is need for frequent monitoring and medication adjustments for the nonsurgical approach, the end result can be a perfect 20/20-seeing eye.