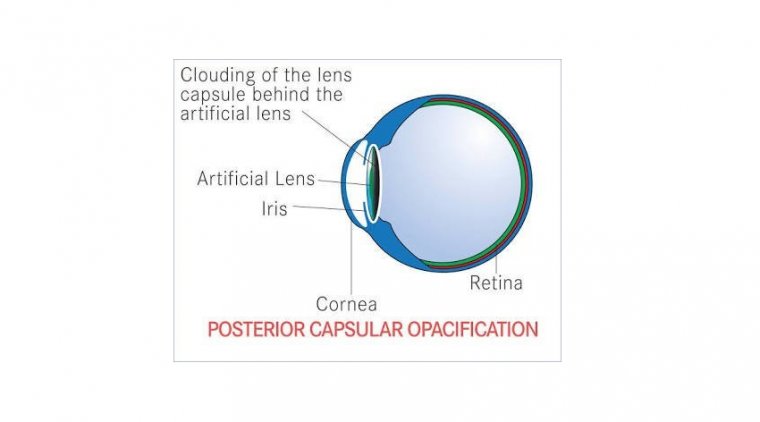

Posterior Capsular Opacification in Preschool- and School-Age Patients

Despite substantial improvements in cataract surgery techniques and intraocular lenses (IOLs), posterior capsular opacification (PCO) continues to be the most frequent postoperative complication of pediatric cataract surgery.

Age is the main factor in PCO development, with the incidence increasing as age decreases. PCO development has been reported in up to 100% of infants after cataract surgery.

Performing posterior capsulotomy and anterior vitrectomy in the same surgical session as cataract extraction is effective in preventing PCO obscuring the optical axis.

However, in necessary cases and with cooperative patients, especially school-aged children whose posterior capsule is intact, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser capsulotomy is another treatment option for PCO.

In patients not suitable for laser therapy, anterior vitrectomy and posterior capsulotomy can be performed via the pars plana approach.

Cataract in childhood is the most important cause of visual impairment and blindness. Lack of vision in early years of life can adversely affect the overall development of the child with far reaching effects on personal, educational, occupational, and social aspects.

Pediatric cataracts can be unilateral or bilateral. They can be subdivided based on morphology, as well as on etiology. The visual results of cataract surgery in children have generally been poorer than in adults.

This difference is owing to the various types of amblyopia that develop in children with cataracts, the association of nystagmus with early-onset cataracts, and the presence of other ocular abnormalities that adversely affect vision in eyes with developmental lens opacities.

Early detection and treatment is crucial for maximizing visual development and preventing amblyopia.

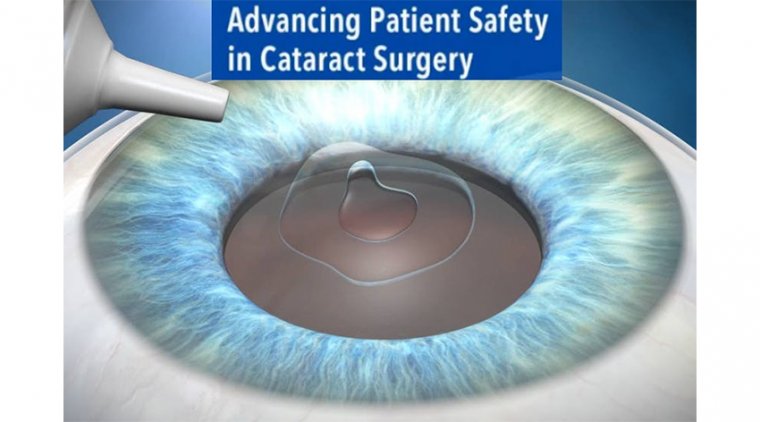

Cataract surgery in children is challenging because of the likelihood of posterior capsule opacification. This can be overcome with primary posterior laser capsulotomy coupled with bag-in-the-lens technology.

In children, the high activity of lens epithelial cells and exaggerated postoperative inflammation induce a greater propensity for posterior capsule opacification (PCO).

The prevention of PCO focuses on surgical techniques, changes in intraocular lens (IOL) material and designs, pharmacologic methods, extensive intraoperative polishing of the anterior and posterior capsules, the use of lenses with posterior convexity to ensure closer IOL-capsule contact, and application of several antimitotic drugs or anti-lens epithelial cells immunologic agents.

Introduction of new microsurgical techniques, instrumentation, and high-molecular-weight viscoelastic has enabled surgeons to remove cataracts safely at an early age.

In the management of surgical aphakia, which can be as amblyogenic as the cataract itself, the various options available include spectacles, contact lenses, and recently, primary implantation of IOLs.

Postoperative opacification of the posterior capsule is one of the major concerns in pediatric cataract surgery.

Paediatric cataract is a major cause of visual impairment in young patients. Although operating on congenital, early childhood or juvenile cataract can be challenging, in the hands of an experienced surgeon and a specialised team, the hurdles posed by the conditions of a developing eye can be overcome.

The bane of the management of paediatric cataract, however, is posterior capsule opacification (PCO), which develops rapidly in the weeks and months after lens removal. Close to or as much as 100% of young children will develop PCO as the most frequent complication in paediatric cataract surgery.

Leaving the posterior capsule intact has been recognised for quite some time as a prerequisite in the pathogenesis of PCO and interventions on the posterior capsule have been introduced as a means to prevent or at least reduce the probability of PCO formation.

The introduction of the femtosecond laser into cataract surgery has been—at least in our view, as pioneers of laser cataract surgery (LCS) in central Europe and with experience of close to 10,000 interventions now—a game changer in many respects.

Primary Posterior Laser Capsulotomy

Posterior capsulotomy has been described as an option for reducing PCO formation in paediatric cataract patients. In our experience, primary posterior laser capsulotomy (PPLC) is a completely new approach, not least because an anterior vitrectomy is usually not necessary.

This in turn reduces the risk of one of the most vicious complications of early childhood cataract surgery, aphakic glaucoma, significantly—in fact, to zero. Aphakic glaucoma is one of the most damaging and most difficult-to-manage forms of glaucoma.

In PPLC, the anterior hyaloid membrane of the vitreous stays intact and thus the influence of vitreous substances (which are discussed among the probable causes of aphakic glaucoma) is reduced to nil.

When undertaking LCS in paediatric patients, we perform capsulotomy with the laser; unlike in adult LCS, the lens is not fragmented because it can usually be removed by aspiration only.

Under general anaesthesia, the child is placed under the laser, then the smaller fluid-filled interface will be slowly and cautiously lowered towards the eye.

After gently connecting with the ocular surface, the laser will perform anterior capsulotomy; when entering the clinical data in the platform’s software, we use the Bochum correction formula.

Anterior capsulotomy is performed and small tags—which appear rarely— are gently removed manually. The posterior capsule is meticulously polished; in paediatric cataracts, pupil dilation tends to be suboptimal.

Ophthalmic viscosurgical device (OVD) is introduced sparingly to avoid pushing the posterior capsular too far back. The posterior capsule is elevated by OVD injection through a small opening in order to change its shape from concave to more convex.

After lens removal under the operating microscope, the young patient is once again positioned under the laser. Primary posterior laser capsulotomy is performed after perfectly aligning the anterior and the posterior capsules. The laser shots are fired from posterior towards anterior.

Bag-in-the-lens

The bag-in-the-lens (BIL) implant or BIL lens is a foldable hydrophilic lens, which consists of a biconvex optic and two elliptical plane haptics and is prepared in a cartridge for implantation.

In adults, it requires a main incision of about 2.8 mm, but a special BIL lens for paediatric eyes is commercially available, which is smaller than the one implanted in adult eyes and can be exchanged when the child is older.

As first described by Marie-José Tassignon in 2002, during the BIL technique with two well-centred capsulotomies of almost identical size, anterior and posterior capsules are placed in this special IOL’s flange for insertion.

We implant the lens by aligning the lower haptic to the 6 o’clock/12 o’clock meridian. A small spatula is used to protect the IOL from going too deep into the anterior chamber during implantation.

When the BIL lens is completely inserted and unfolded, the posterior haptics are placed behind the posterior capsule and the anterior haptics in front of the anterior capsule, which keeps both capsules in the “groove” that is so characteristic of this innovative type of IOL.

This procedure allows perfectly centrated and stable positioning of the lens. Intraoperative use of acetylcholine ensures that the iris covers the haptics. In older children, we make sure the incisions are not leaking; in younger children we use a suture for watertight wound closure.

Minimal remnants of OVD will be resorbed over time. Postoperative care is as usual for paediatric cataract patients except for the additional postoperative application of pilocarpine 1% three times daily for 2 days starting directly at the end of the procedure.

PPLC is generally a safe and effective procedure; we have documented its excellent safety profiles after 6 months and our 2-year results are currently under review. The same can be said about the BIL technology.

A recent publication demonstrated that this implant does not induce an elevated risk for postoperative cystoid macular oedema.

The superiority of secondary BIL implantation over ciliary sulcus implantation of an IOL in aphakic children, in terms of fewer adverse effects, best-corrected visual acuity and IOL centration, was recently described by Liu et al.

Our opinion that cataract surgery has a great tool promising much lower PCO rates in children than could have been hoped for just a year ago is supported by a 2022 publication from Norway: in 50 eyes of 30 patients younger than 12 years at the time of operation, who had received a BIL since 2013, 92% had a visual axis free of PCO.9 In our experience PCO occurs only if the capsule edges are not positioned in the optic groove between both haptics.

This is promising data indeed. And yet, cataract surgery in children is always just the fi rst step on the long and winding road to optical rehabilitation.