The Use Eye Drops for Cataract Surgery

Eye drops are specifically used to protect the eyes from infection, soothe itching, relieve redness and reduce the inflammation associated with the healing process.

Doctors prefer prescription eye drops to over-the-counter products because they not only treat the after-effects from surgery but also help treat any underlying conditions.

Generally speaking, patient adherence to using eye drops is poor, with studies suggesting an overall nonadherence rate of about 30%. Patients’ belief in the utility of the eye drop, remembering to use it regularly, cost, and access to medication are concerns across a variety of disease states.

However, most of what is known about drop adherence has been learned in the context of chronic topical therapy for glaucoma. According to a recently conducted review of the literature on medication adherence after cataract surgery, it has come more clear that the problem of patient non-adherence in this context may be more substantial, albeit unintentional.

The biggest reason for that is, most patients undergoing cataract surgery are typically in the age group most likely to have difficulties in instilling eye drops, including problems with manual dexterity, tremor, difficulty tilting the head back, visual impairment, and conditions that affect hand strength and the ability to open and squeeze a bottle.

Older patients also may have cognitive or memory problems that impair their ability to adhere to a drop schedule.

In a prospective Canadian study in which patients who had cataract surgery were video-recorded instilling their drops on postoperative day 1, only 7% of the 54 patients did everything right. Most patients missed their eyes completely (31.5%), instilled the wrong number of drops (31.5%), failed to wash their hands (77.8%), and/or contaminated the bottle tip (57.4%).

Prescription Details

Odds are against success when it comes to eye drops in the cataract surgery population, thanks to the complexity of the regimen. Doctors typically prescribe an antibiotic, asteroid, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), each of which has a different instilling schedule.

Patients may also be using drops for pre-existing conditions, such as glaucoma or dry eye. They may be instilling up to 14 drops per day from 4 or more bottles following the first eye surgery, and then a different schedule for the second eye a few weeks later.

The confusion can be compounded when, because of insurance restrictions, the pharmacy fills a prescription for a branded qd topical NSAID with a tid or qid generic substitution, necessitating major changes in the drop schedule instructions.

If patients followed medical instructions to wait 15 minutes between drops to avoid washout, their entire day could revolve around drop schedules. This is burdensome for patients and their family members or caregivers.

Even when they do instill the drops on schedule, there is the challenge of getting a topically applied drug to the target tissue inside the eye. In addition to the problem of the drops landing on the lids, cheek, or lashes, physiological barriers including reflex tearing and the tight junctions of the corneal epithelium mean that only 1% to 7% of the instilled drug reaches the aqueous humor.

With steroid drops, patients often fail to vigorously shake the bottle long enough to achieve a homogenized suspension of the active ingredient. This can lead to the patient getting mostly vehicle and very little drug during the initial weeks after surgery, and too much drug later in the course of therapy.

How To Fix The Problem

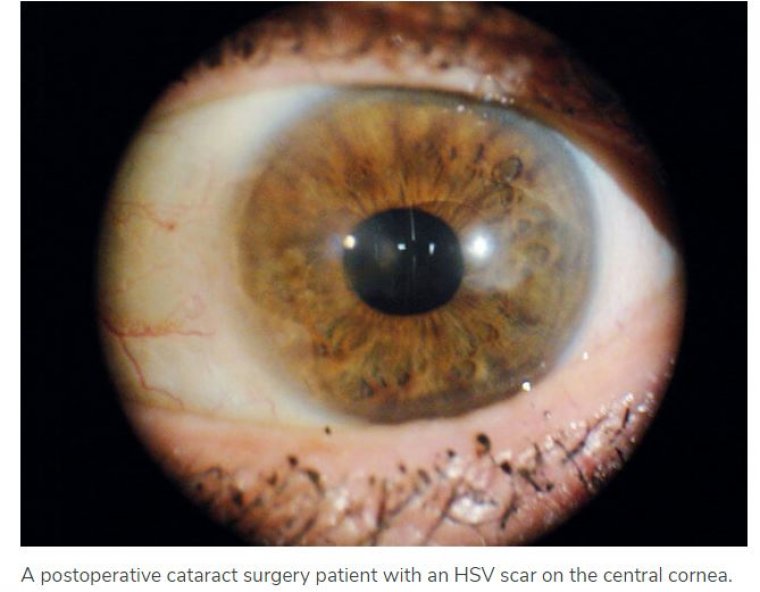

Increasingly, doctors have become convinced that wherever possible, they should move away from topical regimens following cataract surgery. The consequences of missed or incorrectly instilled doses can range from mild corneal edema, discomfort, and slower visual recovery to an increased risk of corneal abrasions, cystoid macular edema, and endophthalmitis.

Through a combination of sustained-release technologies and compounded medications, it is possible to eliminate some or all postoperative drops. For surgeons who have not used any of these options, we very strongly encourage our colleagues to first consider how comfortable they are with compounded medications vs FDA-approved drugs.

Although compounded injections and topical drops are legal, some clinicians or facilities are less comfortable using them. Next, we would suggest replacing 1 topical therapy at a time.

The prime candidate for elimination is the topical steroid because it contributes the greatest complexity to the regimen, with a long duration of use that is complicated by a tapered instilling schedule and, often, the requirement to shake the bottle.

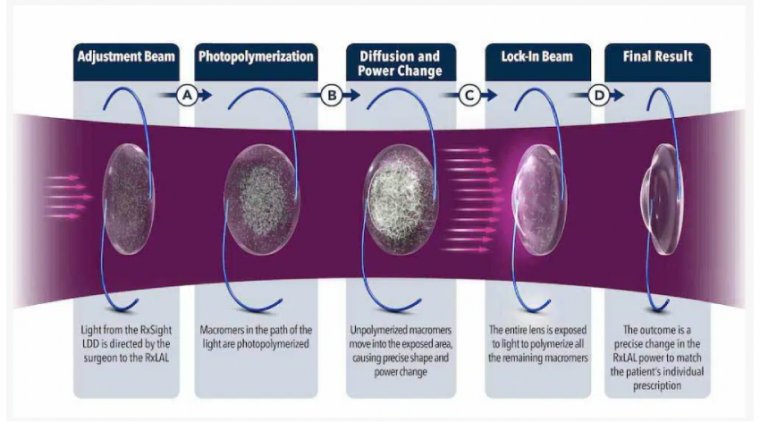

Some doctors now have compounded steroid injections or combination drops from ImprimisRx and Ocular Science, and 2 FDA-approved sustained-release dexamethasone products (Dexycu, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, and Dextenza, Ocular Therapeutix) to reduce the adherence burden on patients and give surgeons more control over the delivery of the steroid.

Dexycu is a biodegradable, extended-release formulation of dexamethasone 9% that is injected into the ciliary sulcus or into the capsular bag at the end of cataract surgery, where it delivers a tapering dose of steroid for the first few weeks after surgery.

In a randomized, controlled clinical trial, complete anterior chamber cell clearing was achieved in 60% of the Dexycu eyes versus 20% in the placebo group at postoperative day.

Dextenza is a bioerodible 0.4-mg dexamethasone insert that can be placed in the lower canaliculus before, during, or after cataract surgery, where it releases steroid onto the ocular surface for 30 days.

In clinical trials, it resulted in less pain and inflammation than a placebo insert. Patients greatly prefer these sustained-release options over topical steroid drops.

Both are FDA approved and have pass-through status, so their cost is typically covered by Medicare or private insurance. Intracameral dexamethasone has the advantage of being applied much closer to the target tissue than topical or intracanalicular options.

It does not have to cross the corneal and conjunctival barriers; instead, the surgeon places it under the iris and near the ciliary body, where the inflammatory cascade begins. When we participated in the Dexycu clinical trials, we noticed how quiet the anterior chambers appeared postoperatively, with hardly any cell or flare on postoperative day 1.

We attribute this to not only the site of injection but also the timing. With topical drops, although we instruct the patient to instill the steroid 4 times a day starting several hours after surgery or starting the next morning if the eye is patched at the time of surgery.

But the reality is that family members may still need to make a trip to the pharmacy, or the patient may go home and fall asleep before instilling the drops.

It can be from 12 to 24 hours or more before the first dose of topical steroid is delivered to the eye, compared with just a few seconds when the surgeon injects Dexycu after the case.

There is a bit of a learning curve for the proper injection technique for Dexycu; there is also the possibility of migration of the dexamethasone spherule onto the IOL optic or onto the iris, where it becomes visible until its absorption within a few days.

With intraoperative sustained-release steroids— perhaps coupled with other injected or sustained-release drugs—we can eliminate the gambles of patient adherence.

This has the potential to greatly enhance the patient experience, improve practice flow, and provide the surgeon with more control over unwanted postoperative complications.