My Algorithm for Cataract and Glaucoma Patients

AI algorithms applied to fundus photographs for screening purposes may provide good results using a simple and widely accessible test. However, for patients who are likely to have glaucoma more sophisticated methods should be used including data from OCT and perimetry.

Outputs may serve as an adjunct to assist clinical decision making, whereas also enhancing the efficiency, productivity, and quality of the delivery of glaucoma care. Patients with diagnosed glaucoma may benefit from future algorithms to evaluate their risk of progression.

The application of my personal algorithm enables a stratified approach to cataract surgery and glaucoma treatment.

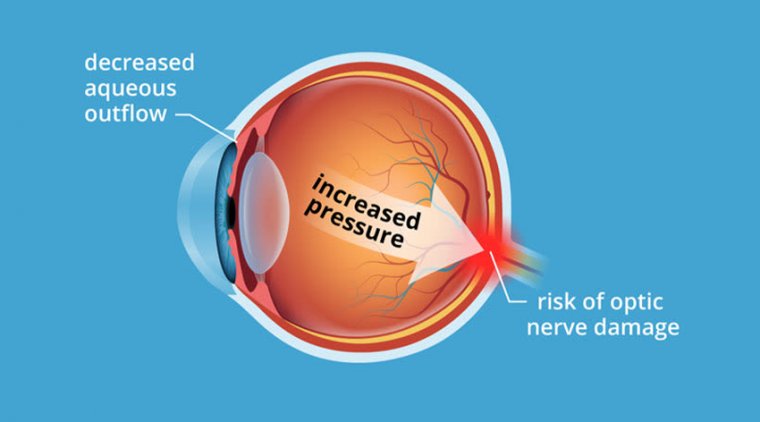

Treating glaucoma in the light of an impending cataract surgery is dependent on the patient’s current disease status – with intraocular pressure, current medication burden, and angle anatomy being the biggest features.

The damage that has occurred to the optic nerve is a minimal factor, as we think that reducing patients’ dependence on drops is always beneficial, even when patients are well controlled.

One thing that does often bridge all disease statuses when strategizing cataract surgery on a patient with glaucoma and who is on IOP lowering mediations, is a Schlemm’s canal-based MIGS procedure.

In our opinion, the canal is the safest site available for a stent or another MIGS device, so it is always my “go to” for cataract surgery, regardless of disease stage. We outline here how we alter treatment for patients, depending on the severity of their glaucoma.

Mild to Moderate

Most cataract patients with concomitant glaucoma fall into the mild to moderate category. Essentially, if the angle is open, IOP is ≤ 25 mmHg, and the patient is on three or fewer medications, then we will implant second or third generation trabecular micro-bypass stents (iStent inject or iStent inject W, Glaukos).

For surgeons who are starting out on stent implantation, gonioscopy is an essential skill. As a first step, we recommend simply beginning to look at the angle using a gonio lens in the clinic or at the end of a cataract case.

There is immense variation in the angle, and taking the time to learn this aspect of ocular anatomy serves surgeons well.

From there, one can progress to using a Sinskey hook to touch the trabecular meshwork (TM) at the end of the case to get a better feel for how to approach the angle and TM during a MIGS procedure.

To make life easier for initial cases, we recommend choosing patients with wide open and well-pigmented angles.

The pigment makes it easier to see the “landing zone” for the stents – in our experience, it generally takes surgeons about 15 procedures to be able to repeatably implant the stents in the correct location.

The latest-generation iStent inject

W has a wider flange, making over-implantation less likely, but there is a learning curve no matter which stent one uses. The postoperative course with stent technologies is fairly similar to that of cataract surgery alone, making them relatively easy to incorporate into a busy cataract practice.

While day one IOP spikes may be a concern after the procedure, we have found it rare during our decade of implanting stents.

Our practice has benefited from not only addressing the patient’s glaucoma longterm, but also proactively blunting any postoperative IOP spikes following cataract surgery, thereby protecting the optic nerve, which has effectively lowered the threshold for implanting stents independent of optic nerve status or preoperative IOP control.

Narrow angles and moderate glaucoma

For patients in the IOP range of 25–35 mmHg, we often combine the use of catheterization and viscodilation with a stent. For those with narrow angles, we rely on ab-interno canaloplasty (ABiC) for catheterization and viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal using the iTrack microcatheter (Nova Eye Medical).

When considering narrow angle patients, the surgical decision making must be adjusted. For some patients – such as those on one medication before the operation – no additional glaucoma procedure is needed; the narrower the angle, the greater the IOP-lowering effect of cataract surgery.

Narrow angles, especially in the setting of a higher iris insertion, increase the risk of iris prolapse into the stent device. In cases with narrow angles, when a MIGS procedure is desired, a dilating procedure, such as ABiC or canaloplasty with the Omni Surgical System (Sight Sciences), is a safer approach.

We often don’t make the final decision of which procedure to perform until we have had the chance to inspect the angle and iris insertion intraoperatively. Similar to stenting, surgeons who want to perform ABiC should focus initially on gonioscopy skills.

The ABiC procedure requires many more steps and the assistance of a good technician – as well as the surgeon’s good situational awareness and comfort in visualizing through blood. We like to fill the eye exuberantly with viscoelastic, because having a slightly higher pressure in the anterior chamber reduces bleeding and enables a better view.

While overfilling the anterior chamber when stenting can collapse Schlemm’s canal, that is much less of a concern when catheterizing the canal. The illuminated distal tip of the catheter provides good viewing of the canal, so it is helpful to turn off the microscope light to check positioning.

Advanced Glaucoma

For patients with a very high IOP >35 mmHg, we prefer gonioscopy assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT), which we also perform with the iTrack microcatheter. This more invasive procedure is one that I reserve for patients with a more severe disease – or a more unstable IOP.

The GATT procedure is very similar to ABiC, but requires a little more dexterity to grasp the leading end of the catheter through the TM with the dominant hand, while using a tying forceps in the nondominant hand to hold the other end of the catheter, to create a 360° trabeculotomy.

Again, using a generous amount of viscoelastic is the key to good visualization, and some surgeons will leave a small amount of viscoelastic in the eye to prevent bleeding from the canal. At the end of the case, it is important to evacuate as much of the blood as possible.

We instruct the patient to avoid exertion for the first week after GATT, and to sleep with the head slightly elevated to reduce the venous return and episcleral venous pressure.

It may be helpful to sleep on the side of the operated eye (left cheek to the pillow if the left eye was operated on) to further reduce pressure by elevating the nasal episcleral vessels.

We do follow GATT patients a little more closely afterwards because of the expected bleeding – typically seeing patients weekly until any hyphema has cleared and vision returned, usually by three weeks.

Eyes that have had a GATT procedure are also more prone to postoperative inflammation, so steroids may be needed for a longer duration postoperatively.

A bridge to filtering surgery Increasingly, we are also using canalbased MIGS as a bridge therapy for patients with advanced disease who will ultimately need a filtering procedure, like trabeculectomy or a PRESERFLO MicroShunt (Santen).

This approach allows to safely remove the cataract in more complex glaucoma patients and improve their ocular surface in preparation for later trabeculectomy. There is very good evidence that filtering surgery success rates are affected by the health of the conjunctiva, which is compromised by dry eye or meibomian gland disease.

We have one patient who had trabeculectomy surgery in 1989. Today, at 93 years old, he still has an IOP of 10 mmHg OU. Many of us have such longterm success stories in our practices from the days when patients underwent earlier trabeculectomy – while they still had a pristine ocular surface.

Although modern glaucoma medications have helped to preserve vision and avoid the need for filtration in many cases, there is no doubt that they are toxic to the ocular surface – and that damage cannot be reversed in a matter of days or weeks.

We have found that cataract surgery with a stent or canaloplasty procedure can reduce the medication load for these patients.

We also switch to preservative free options for any remaining drops and allow the ocular surface to heal for six to 12 months before attempting trabeculectomy – anecdotally, we find this leads to superior results.

We are fortunate to be able to titrate MIGS to the patient’s IOP and anatomy. At all stages of glaucoma, canal-based MIGS procedures at the time of cataract surgery can help to preserve vision through reduced IOP – both minimizing the chance of postoperative IOP spikes that can damage the optic nerve, and reducing the medication burden to improve ocular surface health and patients’ quality of life.