Cataract Surgery & Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD)

Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is the most common indication for corneal transplantation around the world, comprising 39% of all transplant operations.

A thorough history can be helpful in the evaluation of patients in whom there is a concern for FECD. Classically, patients report blurred vision that is worse upon waking, which then improves throughout the day as the cornea deturgesces naturally.

FECD patients may also report glare. In later stages of the disease, if edema has progressed to the formation of epithelial bullae, patients may present with pain upon bullae rupture. Female gender and smoking history have been associated with a greater risk of advanced disease, and should be assessed.

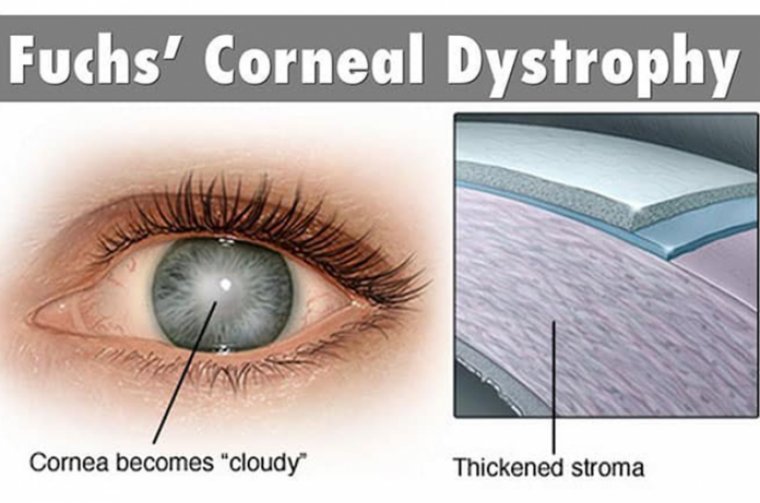

Careful slit lamp examination for corneal guttae, representing focal excrescences in Descemet’s membrane, is paramount.

Guttae appear as greyish, dimpled foci at the level of the endothelium. The location (central versus peripheral), confluence, and total diameter of guttae should be noted. The presence of guttae peripherally may signify more advanced disease.

The presence of stromal or epithelial edema, epithelial bullae, epithelial defects due to rupture of bullae, and subepithelial fibrosis should be observed as well.

Additional work-up should include specular microscopy, assessing endothelial cell count, and the degree of pleomorphism and polymegathism present to document the extent of the disease, and the need for surgery.

Central corneal thickness measurements should also be performed routinely, most importantly for gauging progression of the disease. Population data demonstrates variability, and does not offer clear pachymetric cutoffs for the assessment of corneal edema.

Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is a bilateral corneal endothelial disorder, affecting predominantly those in the 4th to 5th decade of life, characterized by accelerated loss of endothelial cells, thickening of Descemet’s membrane, and subsequent dysfunction of the endothelial pump function responsible for maintaining corneal dehydration and clarity.

The resulting corneal edema affects vision and, in time, can lead to epithelial bullae, and subepithelial scarring.

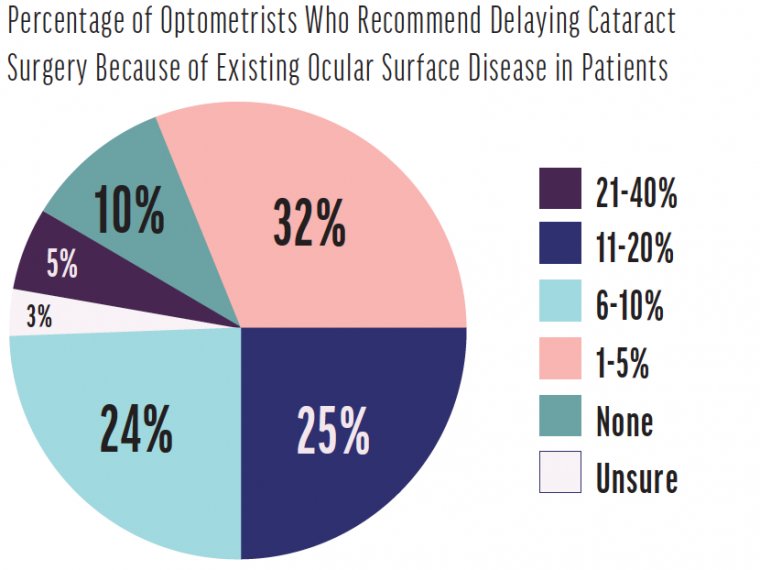

As cataracts and FECD both often become clinically significant at nearly the same time, it is important for the surgeon to determine which condition to address first, in what sequence, and whether they should be addressed simultaneously.

In general, corneal endothelial transplantation can be performed either in conjunction with cataract surgery in FECD patients, or subsequently in a staged fashion.

A large, retrospective case series demonstrated no difference in visual acuity or graft survival between Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) (often the procedure of choice) cases performed in phakic versus pseudophakic eyes.

Here’s a look at the considerations for cataract surgery alone, descemetorhexis without keratoplasty, endothelial transplant alone, and a concomitant procedure in FECD patients.

Of note: PK has largely been replaced by DMEK and “nano-thin” Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) for FECD patients, as the recovery time and final visual acuity are much better than with PK.

Nevertheless, PK is occasionally needed in cases in which FECD has advanced to the point where there is full-thickness corneal scarring.

Cataract Surgery Alone

Typically, it is felt that cataract surgery should precede endothelial transplantation when possible, so as not to stress the transplanted endothelial cells during phacoemulsification.

Surgeons should always obtain topography and standard biometry in cases of FECD. This is because corneal topography and keratometry in these patients can be irregular, especially in advanced FECD, causing standard keratometry readings to sometimes be misleading.

Additionally, bullae or microcystic edema can cause significant distortion of the anterior corneal surface, and stromal edema can mimic corneal ectasia on anterior topography.

Regarding patient candidacy, those who have confluent guttata without overlying edema may be able to undergo cataract removal alone, but need to be warned of the risk of corneal decompensation postoperatively.

Likewise, significant guttata alone can be visually symptomatic, causing glare, so it is reasonable to consider combined surgery in these patients.

In patients who have pre-existing, demonstrated regular astigmatism not due to edema, toric IOLs are a reasonable option, as several case series demonstrate good results in toric IOLs minimizing astigmatism, as long as attention is paid to IOL rotation.

Given the difficulty of accurately predicting the refractive outcome following endothelial transplantation, multifocal IOLs may not be appropriate in FECD patients, as there is a high chance these patients will not achieve spectacle independence.

There are reports of successful DMEK following multifocal IOL placement, but at this time only limited case series are available in the literature.

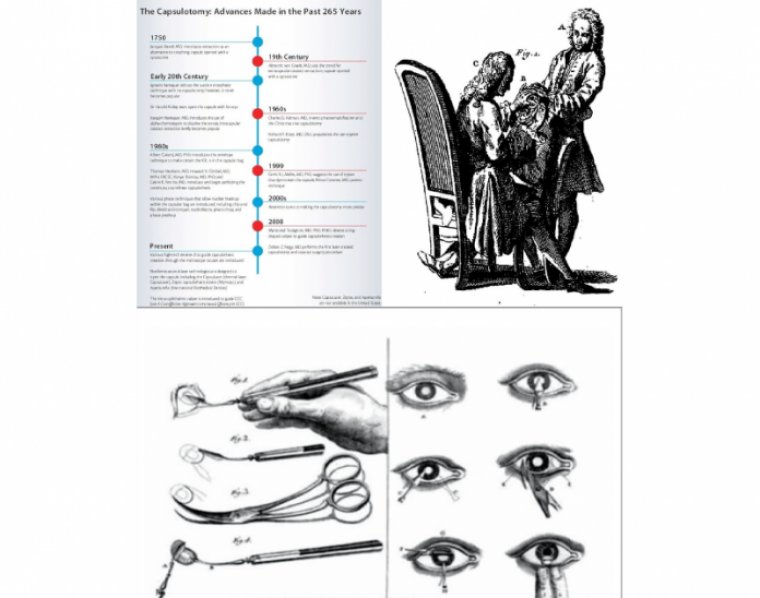

Descemetorhexis Without Keratoplasty

This procedure is typically reserved for patients who have localized, central guttae with adequate peripheral endothelial cell reserve, generally considered to be a peripheral endothelial cell count greater than 1,000 cells/mm2.

In these patients, final visual outcome can be similar to that of DMEK, though time to recovery is longer, and the edema may fail to clear in up to 37% of cases, necessitating delayed endothelial transplantation.

Specifically, a 4 mm circular descemetorexhis is performed centrally using a reverse Sinskey hook to start the process. Reverse Utrata forceps are then used to peel the Descemet’s membrane in a circular fashion, taking care not to damage the underlying stroma.

Peeling rather than scoring is recommended to preserve the attachment of the peripheral membrane to the underlying stroma, and facilitate endothelial migration into the denuded area.

The use of a topical rho kinase inhibitor in the postoperative period may hasten corneal clearance, although none of these are currently approved for this use in the United States.

Endothelial Transplant Alone

Patients who have more advanced disease, or those desiring more rapid clearing of edema benefit from endothelial transplant.

Although there are no hard-and-fast rules for considering endothelial keratoplasty, generally, patients who have bullous edema or increased pachymetry > 625 um do better with endothelial transplantation.

For these patients, DMEK or DSAEK can be considered.

• DMEK. This offers advantages in visual outcome in straightforward cases of FECD. There is a greater risk of graft dislocation after DMEK versus DSAEK, and the need for postoperative re-bubbling is greater after DMEK, although this has been decreased with the use of 20% sulfer hexafluoride gas for tamponade.

• DSAEK. There is some indication that “nano-thin” DSAEK with grafts less than 50 um may offer similar visual outcomes to DMEK.

Additionally, unstable anterior chamber dynamics, precluding the shallowing required to unroll the DMEK graft, would favor DSAEK as the procedure of choice.

For instance, in vitrectomized eyes, it can be difficult to obtain the level of shallowing required to position the DMEK graft correctly, and postoperative collapse of the anterior chamber may prompt graft dislocation.

If there is any chance of vitreous prolapse with shallowing of the anterior chamber, DSAEK may be a better choice, with or without the preceding vitrectomy.

The postoperative complications for both procedures include pupillary block glaucoma, for which an inferior peripheral iridotomy can be created pre- or intraoperatively.

Graft failure and rejection are also potential complications, and their rates are similar in both operations.

Cystoid macular edema (CME) has been reported after both DMEK and DSAEK as well. One study showed that 13.0% of eyes developed CME within 6 months of DMEK, and that visual outcomes were comparable with the remaining patients at 6 months with only medical treatment.

Another study revealed iris damage and re-bubbling as risk factors for the development of CME status post-DMEK.

Concomitant Procedure

Generally, central corneal thickness > 640 μm and/or endothelial cell count < 1000/mm2 may be suggestive of corneal decompensation with intraocular surgery.

Patients complaining of morning visual blur that improves throughout the day are good candidates for simultaneous or staged endothelial transplantation, as they already have developed edema.

Likewise, patients with evidence of stromal edema on examination, grade 5 corneal guttata, or epithelial bullae should also be offered combined surgery.

Care should be taken to acquire accurate biometry calculations, as well as corneal topography preoperatively, if concomitant cataract surgery is planned.

Endothelial transplantation does induce a hyperopic shift due to changes in corneal refractive power, so this should be accounted for in IOL selection. A refractive target of -0.75 D may be sufficient to overcome this shift, and yield an emmetropic result.

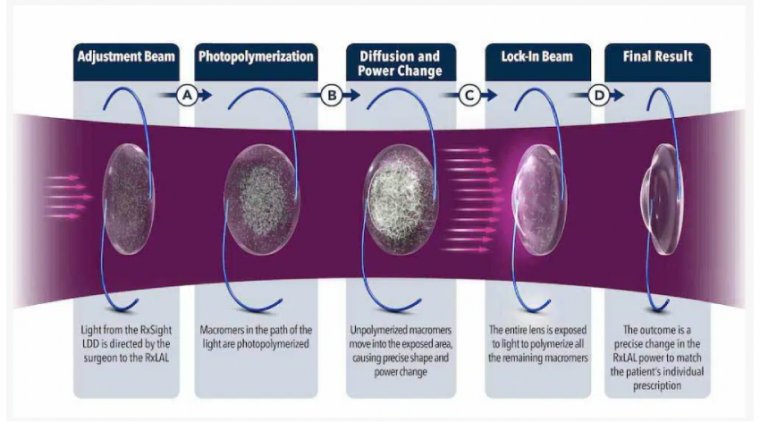

Progress

There has been a great deal of advancement in both endothelial transplantation and IOL technology over the last two decades. With an abundance of options available, FECD patients are well served. Moreover, further innovations are on the horizon.