Dysphotopsia & Cataract Surgery

Dysphotopsia is one of the most under-recognized complications following otherwise unremarkable cataract surgery.

Unwanted optical images are a leading cause of patient dissatisfaction after uncomplicated cataract surgery.

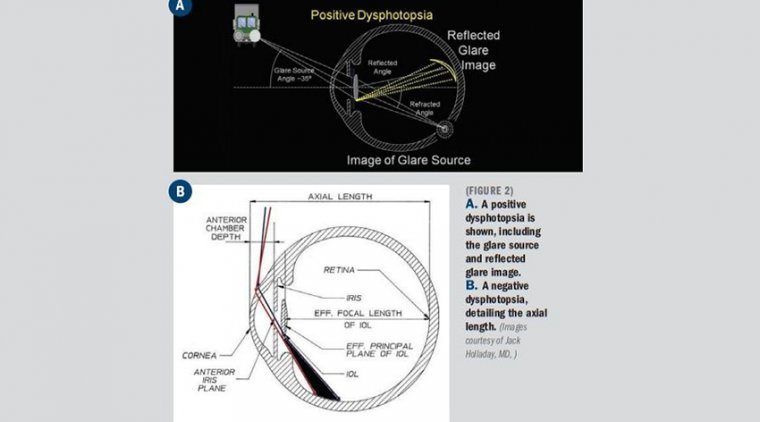

This includes dysphotopsias, or undesirable optical patterns on the retina. Positive dysphotopsia (PD) is a bright artifact of light, described as arcs, streaks, starbursts, rings, or halos occurring centrally or mid-peripherally.

Negative dysphotopsia (ND) is the absence of light on a portion of the retina described as a dark, temporal arcing shadow. The exact nature of these events is incompletely understood, but there are many different theories with both clinical and laboratory evidence to support them.

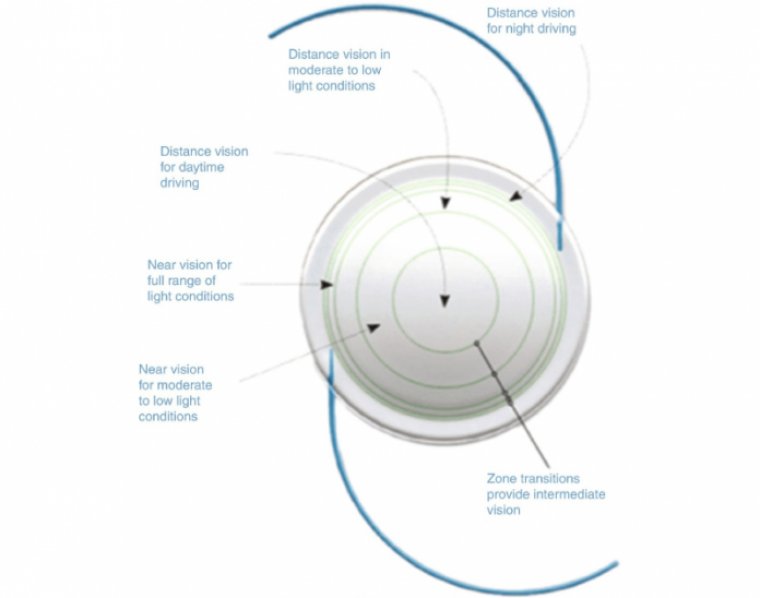

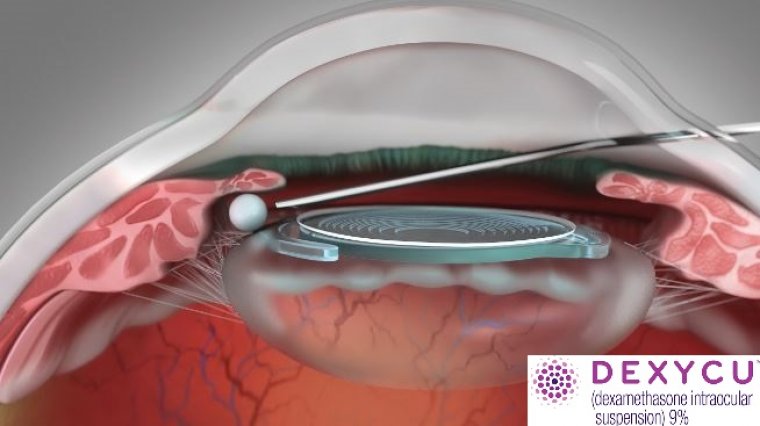

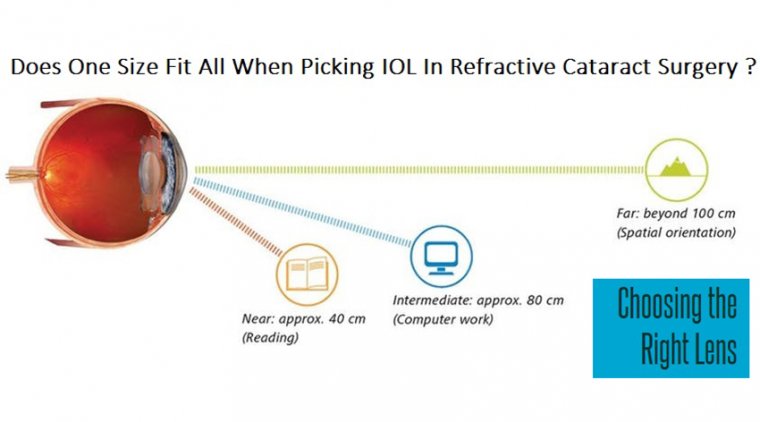

At present, it seems that PD is related to intraocular lens (IOL) material, design, and location, while ND is multifactorial in origin, primarily contributing to an illumination gap causing a shadow on the retina.

ND is more complex to analyze but may benefit from improved IOL design as well as varying the surgical approach of IOL implantation. While most patient experiences of dysphotopsia resolve or undergo neuroadaptation, persistent symptoms can occur and warrant surgical consideration.

Based on subjective symptoms, up to 20% of patents have negative dysphotopsia (ND), a temporal dark shadow after IOL implantation.

Other patients have positive dysphotopsia (PD), characterized by light streaks, arcs, central light flashing or star bursts. Some patients may have both ND and PD. “Overall, dysphotopsia has not been studied particularly well.

Surgeons can’t discount dysphotopsias, either positive or negative, after cataract surgery and IOL placement. The literature suggests that dysphotopsias are relatively rare, but patient reports suggest a different story.

“If you ask patients, it can be almost 50% immediately after surgery,” said Nick Mamalis, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Utah John A. Moran Eye Center in Salt Lake City.

“The majority of these just go away or patients get used to them. But for an important minority of patients, these are significant visual issues and they don’t improve as time goes on.”

Positive dysphotopsias produce visual artifacts that appear as areas of bright light, streaks, and flashes central in the visual field. Negative dysphotopsias produce dark temporal shadows that mimic the effect of blinders worn by racehorses.

Both positive and negative dysphotopsias are associated with the IOL material, design and placement, Dr. Mamalis noted.

Positive dysphotopsias are most often characterized by persistent bright rings, flares, arcs, halos, and flashes that most often appear when light is coming into the eye from the side, such as the oncoming headlights of another vehicle.

The long-term incidence may be as high as 1.5% and can vary greatly by IOL type, material, and design Positive dysphotopsia was first reported in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), the material most commonly used during the early development of IOLs.

Symptoms were generally minor glare and transient. Hydrophobic acrylic lenses are more prone to positive dysphotopsia. The higher index of refraction is more likely to result in internal reflections when exposed to bright sources.

Silicone lenses are rarely associated with positive dysphotopsia, possibly because of lens design. Lenses with square edges, typically hydrophobic acrylic IOLs, are associated with an increased incidence of positive dysphotopsia.

Frosted and textured edges as well as beveled designs have been used to reduce the intensity of stray reflections and reduce the incidence of positive dysphotopsia. Treating positive dysphotopsias is relatively straightforward.

Explanting and exchanging the original lens with an IOL that has a different material or edge design usually reduces or removes the problem entirely. PMMA, silicone, and hydrophilic acrylic lenses with edge designs that are not square are reported to help resolve positive dysphotopsias.

“Negative dysphotopsias are completely different,” Dr. Mamalis pointed out. “The more often you ask about negative dysphotopsias, the more frequently patients report those dark temporal shadows, especially in the first couple of weeks.”

About 71% of negative dysphotopsias resolve in the first weeks and months after surgery, he continued. Depending on how and when patients are questioned, between 0.2 and 2.4% have persistent symptoms.

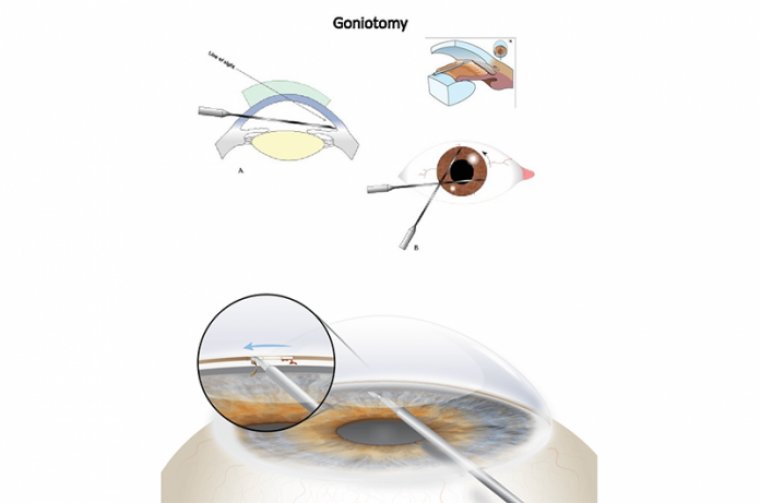

“Do not get too excited at first and try to do something about it immediately,” Dr. Mamalis advised. “In a lot of patients, it goes away.” The etiology of negative dysphotopsias involves the spatial relationships between the IOL, the capsular bag, and possibly the iris.

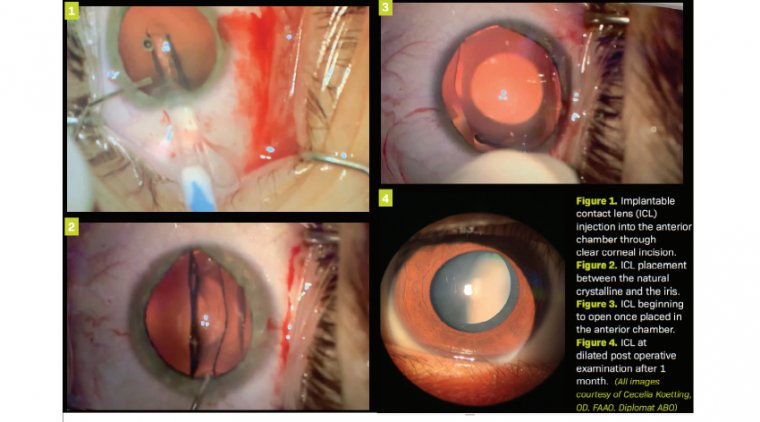

IOLs implanted in the capsular bag or in the posterior chamber are more likely to produce negative dysphotopsias while IOLs implanted in the sulcus or in the anterior chamber seldom do.

Ray tracing suggests that at least part of the problem lies with internal reflections when the lens is placed in the capsular bag that can cast temporal shadows.

Other potential factors include corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, IOL power, axial length, and the distance between the pupil and the implant. “Negative dysphotopsias are seen more frequently in patients who have a square-edge IOL,” Dr. Mamalis said.

“It can occur with any lens material, though we see it more frequently with hydrophobic acrylic.” Treatment typically involves IOL exchange and implantation of a new lens into the sulcus.

Piggyback or add-on IOLs can also help alleviate negative dysphotopsias by diffusing light more effectively before it enters the eye, reducing the potential for shadow formation.

Reverse optic capture, placing the optic over the edges of the capsular bag instead of in the bag, can also help. And some surgeons perform laser anterior capsulotomy to enlarge the capsule opening. New lens designs may reduce the problem in the future.

The Masket lens, with a groove on the anterior surface, allows the lip of the optic to ride over the anterior capsule, reducing the potential for negative dysphotopsias. A bag-in-lens design serves the same purpose, putting the optic atop the bag rather than allow the bag to ride over the edge of the optic.

Another design adds peripheral concavity to the optic to better diffuse light entering the eye, reducing the potential for shadows. “The treatment varies,” Dr. Mamalis said. “Depending on the patient, changes in IOL material, design and placement can decrease or treat these dysphotopsias when they occur.”