How Wine Consumption Reduces Cataracts

New Study Reveals; Wine consumption may reduce Cataracts… Only Wine, Not Other Alcoholic Drinks!

The wine antioxidants play a role in cataract prevention!

People who consume alcohol moderately appear less likely to develop cataracts that require surgery. Wine consumption showed the strongest protective effect, suggesting that antioxidants that are abundant in red wine may play a role in cataract prevention.

However, people who drank daily or nearly daily had about a 6 percent higher risk of cataract surgery compared with people who consumed alcohol moderately.

The study, carried out by a team from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, was published in Ophthalmology (the journal of the American Academy of Ophthalmology).

Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust is one of the leading providers of eye health services in the UK and a world-class center of excellence for ophthalmic research and education.

The research was prompted by inconsistency in the findings from previous studies, which ranged from showing no association between alcohol and cataracts to a reduction in risk from low to moderate levels of consumption, to an increased risk from high consumption.

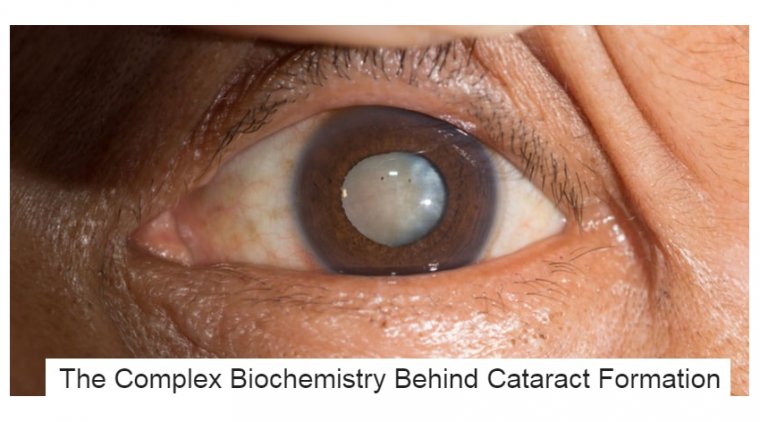

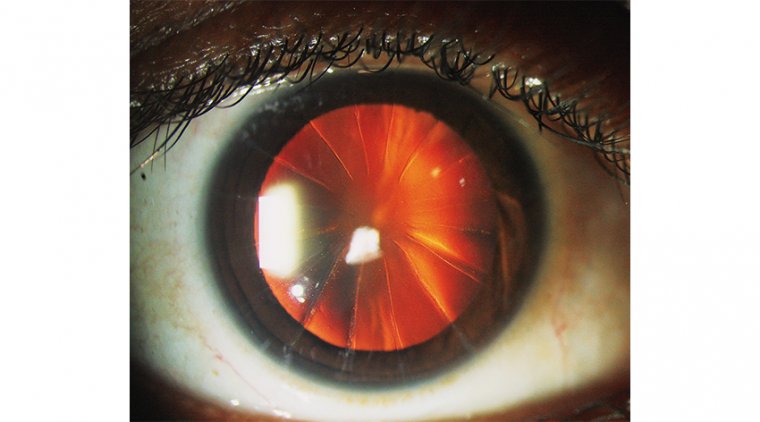

Cataracts are cloudy patches that develop in the lens of the eye and eventually impair sight. They usually affect older people, with an estimated 30% of over-65s suffering visually impairing cataracts in one or both eyes.

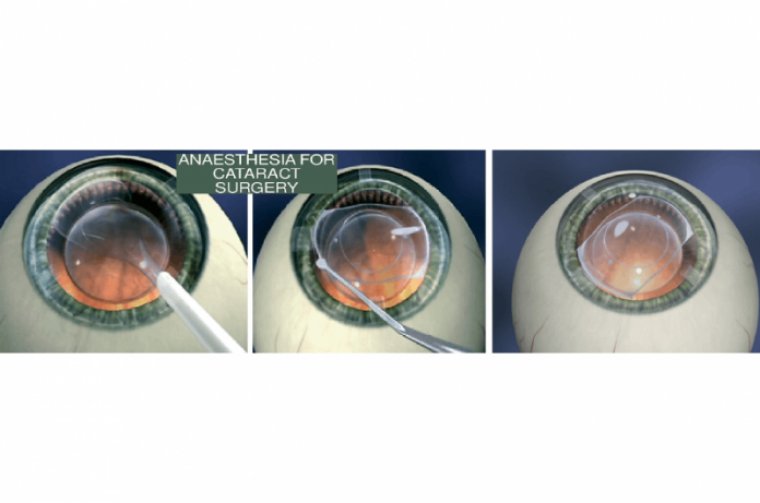

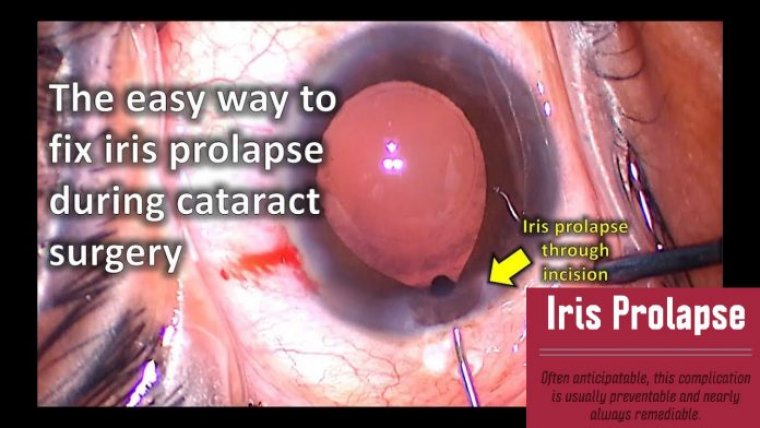

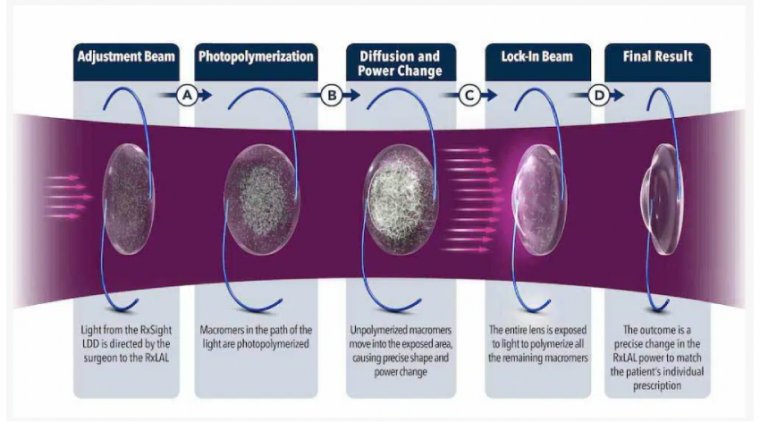

Cataract surgery, where the lens is replaced with a clear plastic one, is currently the only treatment. It is the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the UK, with around 450,000 operations carried out every year in England alone.

This new study is the largest of its kind to date on the association between alcohol consumption and the incidence of cataract surgery. It relied on data from over 490,000 people in the well-established UK Biobank and EPIC-Norfolk cohort studies.

Participants in these studies have volunteered to be followed throughout their lives and give detailed information about themselves and their health, lifestyles, and circumstances.

Due to the large amounts of linked data spanning many years, these studies are particularly valuable for detecting environmental factors associated with disease development and progression.

Dr. Anthony Khawaja, who led the research and was senior author of the paper, said: “We observed a dose-response with our findings – in other words, there was evidence for reducing the chance of requiring future cataract surgery with progressively higher alcohol intake, but only up to moderate levels within current guidelines. This does support a direct role of alcohol in the development of cataract, but further studies are needed to investigate this.”

The researchers compared self-reported alcohol consumption with patient records of cataract surgery. They adjusted the results to take into account factors already known to affect cataracts: age, sex, ethnicity, social deprivation, BMI, smoking and diabetes.

They found that drinkers who consumed alcohol within the maximum UK recommended weekly limit (up to 14 units per week, which equates to about 6.5 standard glasses of wine) were less likely to undergo cataract surgery.

The most significant reduction was associated with wine compared to beer or spirits. For example, participants who drank wine five or more times per week were 23% less likely than non-drinkers to undergo cataract surgery in the EPIC-Norfolk study, and 14% less likely in the UK Biobank study.

However, participants with high beer, cider, or spirits consumption had no significantly reduced risk.

The authors concluded that low to moderate consumption of alcohol, and wine, in particular, appears to lower the risk of developing severe cataracts. Importantly, however, they note that their findings do not yet prove a causal link between alcohol and reduced risk of cataracts and that other unknown factors may be affecting the results.

They also noted that drinking high levels of alcohol is widely linked to many serious and chronic conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Nevertheless, these results should help researchers gain a better understanding of the causes and mechanisms of cataracts, as well as potential treatments, and the authors call for further studies to test their findings.

Commenting on what might lie behind the results, Dr. Sharon Chua, first author of the paper, said:

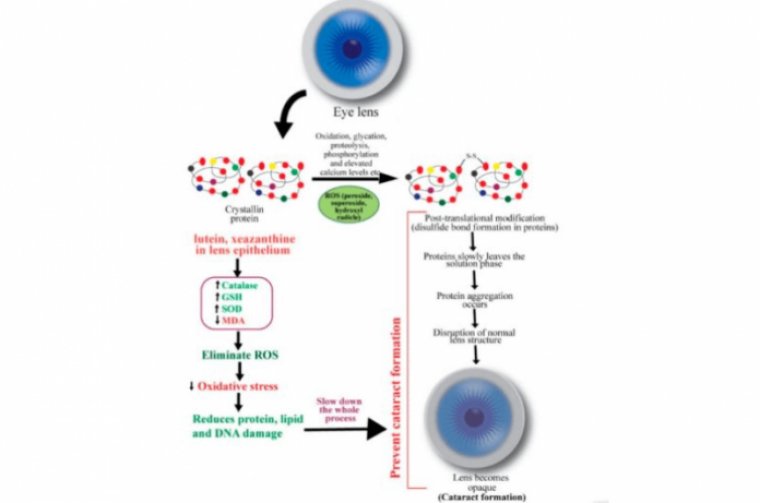

“Cataract development may be due to gradual damage from oxidative stress during aging. The fact that our findings were particularly evident in wine drinkers may suggest a protective role of polyphenol antioxidants, which are especially abundant in red wine.”