The Capsulotomy

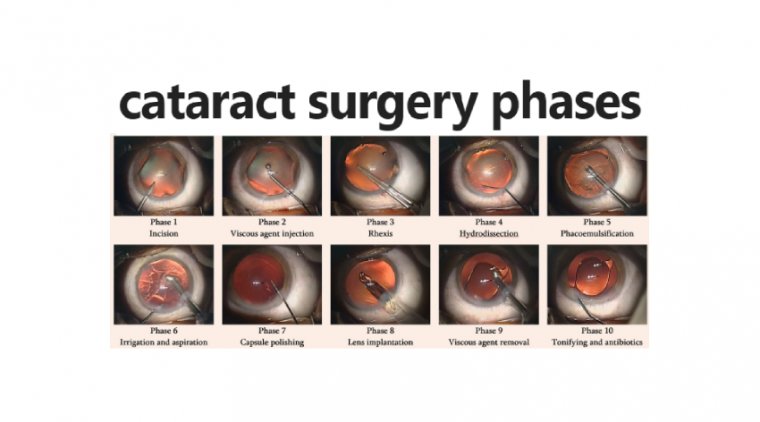

Capsulotomy is a type of eye surgery in which an incision is made into the capsule of the crystalline lens of the eye. In modern cataract operations, the lens capsule is usually not removed.

The most common forms of cataract surgery remove nearly all of the crystalline lens but do not remove the crystalline lens capsule (the outer “bag” layer of the crystalline lens).

The crystalline lens capsule is retained and used to contain and position the intraocular lens implant (IOL). The cuts are made with a cystotome along the periphery of the lens in a circular, jagged configuration (called ‘can-opener’ capsulotomy).

Before the advent of laser surgery, a tiny knife called a cystotome was used to cut a hole in the center of the lens capsule, thus providing a clear path for light to reach the retina. This procedure thus reduces the opacity of the lens of the eye.

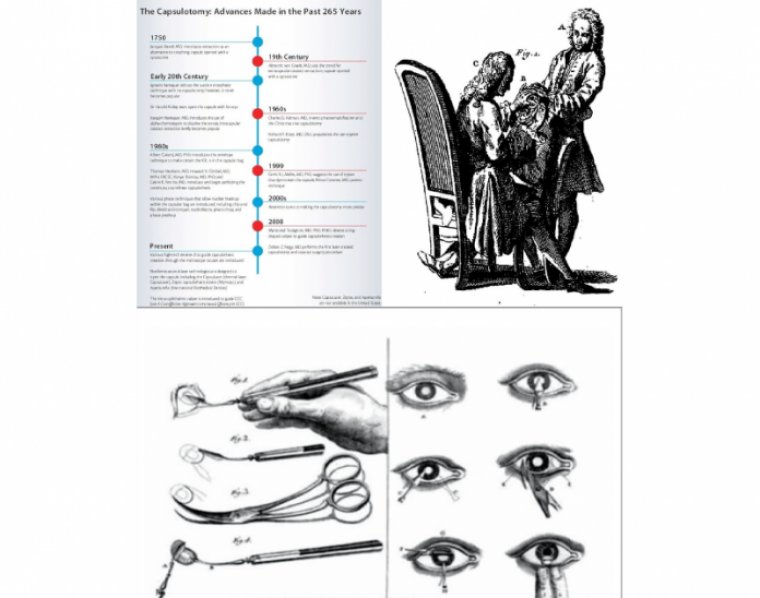

The capsulotomy has a fascinating history – one tinged with jealousy, rivalry, fashion, evolution, revolution and even nationalistic pride – and it’s a story that’s got a great deal more to tell.

It started with the Frenchman, Jaques Daviel, who ushered in the modern era of cataract surgery, abandoning couching for the first extracapsular cataract extraction.

The British, for predominantly patriotic reasons, preferred couching, but ECCE was always going to win out. Albrecht von Graefe improved it in 1850 with his eponymous knife and, extraordinarily, his technique lasted for over a century.

That’s not to say that competing approaches weren’t developed along the way – Ignacio Barraquer devised the suction cup-based erisophake in 1917, which enabled rapid intracapsular extraction of the lens, but its uptake was limited. So the von Graefe method persisted into the 1970s.

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw lensectomy return to an intracapsular approach, thanks to a combination of Joaquin Barraquer’s enzymatic zonulolysis approach and cryoextraction of the lens.

Around that time, Cornelius Binkhorst, one of the pioneers of lens implant surgery, realized that to make intraocular lenses (IOLs) work, you needed to move away from fixation to vital tissues and use the capsule instead.

And that’s why he developed his two-loop iridocapsular lens – and he tried many different shapes of capsulotomy to get the best fixation. We all know the story of how Charles Kelman introduced phacoemulsification in 1967 – and Charlie devised a new way to make the capsulotomy, using a hooked cystitome: the Christmas tree.

However, Kelman was performing anterior chamber phaco – and, to do that, you need to prolapse the nucleus into the anterior chamber. Dick Kratz decided that he would like to perform phaco more in the posterior chamber, so he came up with the “can opener” capsulotomy in the 1970s, which resulted in a ‘roundish’ opening.

Time for CCC

To begin with, the capsular opening was simply to give access to the cataract, but IOLs changed that. We remember being at the AAO Annual Meeting in 1983 when there was a vigorous debate between the people who designed these lenses: Steve Shearing, Bob Sinskey and Dick Kratz, as to whether or not the lens should go into the capsular bag or the sulcus.

The reason for the debate? You really couldn’t guarantee that you’d be able to keep the IOL in the bag with the can-opener capsulotomy. But of course, this all changed with the development of the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC), which is essentially the current state of the art in (manual) cataract surgery.

The CCC meant that IOLs could be placed reliably and securely in the capsular bag – although it did mean that certain procedures needed modification because of the containment by the capsular opening.

And indeed they were. Several new phaco techniques were developed to overcome these difficulties: chip and flip, divide-and-conquer, nucleofractis and phaco chop and prechop.

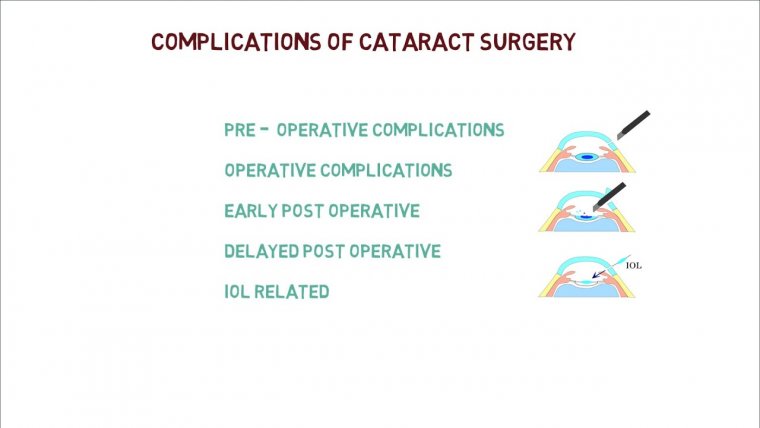

We know that one of the problems with leaving the posterior capsule in place (particularly in children) is that you get posterior capsule opacification (PCO). Howard Gimbel gave us this technique to do a posterior capsulotomy and then capture the IOL optic in it.

Daniele Aron Rosa gave us the YAG laser back in 1982, which wasn’t practicable for anterior capsulotomies, but it reliably performs posterior capsulotomies, and is a standard procedure today for dealing with PCO.

The challenge has always been to make the CCC more precise in terms of size and centration, as this helps with IOL centration, stability, effective IOL lens position, and being able to overlap the edge of the IOL with the capsule and “shrink-wrapping” the lens to lessen PCO. These are important factors, but acutely more so when multifocal and toric IOLs are used.

Then came the femtosecond laser. First used clinically by Zoltán Nagy in 2008, it represented another fundamental change in how capsulotomies are made. For the first time, we could make a truly circular capsulotomy of a pre-specified size in a pre-specified position – without the variables of the manual technique.

But it did come with some caveats. You might need a second room for your laser, which might interfere with your surgical flow.

The device purchase and running costs are high, and as the recent EUREQUO registry publications have shown, there are very few scenarios where patients have derived any benefit over manual cataract surgery where the surgeon performs a CCC, rather than the laser performing a capsulotomy. Might there be other ways of achieving the same consistency and accuracy?

If you’re performing CCCs by hand, you might consider Marie-José Tassignon’s CCC ring; once centered on the capsule, you tear inside it.

Others simply mark the cornea – or use the high-tech equivalent, having it rendered on a head-up display which can be particularly useful when you get a widely dilated pupil or a very large eye.

However, on the horizon, there are a number of new approaches that make the capsulotomy more accurate and precise.

Capsulotomy’s Future Capsulaser

The Capsulaser device is a small laser that is attached under the surgical microscope, and is connected to a small, shoebox-sized console.

t’s a continuous laser, rather than a pulsed laser, and it scans in a single circular pattern over a period of one second to create the curvilinear capsulotomy opening.

It requires the anterior capsule to be stained with Trypan blue, which creates a chromatically selective target for the laser.

The irradiation changes collagen IV to elastic amorphous collagen, and this phase change results in not only a smooth edge but also a very elastic capsular rim (the capsulotomy can be extended from 5 to 12 mm without fracture or tear). And thanks to how the laser works, it’s almost impossible not to get a free cap.

The preliminary results have been good, there’s been no pupil construction after laser use, no untoward anterior chamber activity postoperatively, and in a case series of 20 patients, their corneas remained clear out to 18 months, with similar endothelial cell counts to patients that underwent normal cataract surgery.

Also noteworthy is that these capsulotomies have remained well centered and have not contracted at all – meaning that there’s been no subsequent change in IOL position. To date, another 400 eyes have been operated upon and the CE mark trial has recently been completed.

The device has also been used to perform posterior capsulotomies in cadaver eyes, and what’s interesting here is that it leaves the anterior hyaloid intact.

Zepto

There are also now thermomechanical devices being developed for anterior capsulotomy, like the Zepto device. It consists of a soft, foldable clear suction cap that contains a nitinol capsulotomy ring that’s inserted through a 2.2 mm clear corneal incision using a disposable handpiece.

Once in the eye and aligned over the visual axis, a push rod is retracted and the device unfolds into a circular shape, whereupon the surgeon can center the device and apply suction.

A pulse of electrical energy is delivered in milliseconds to the nitinol ring, triggering a rapid phase transition of water molecules that are trapped between the device and the capsular membrane – instantaneously creating a cleavage plane in the capsular membrane, making a strong capsulotomy. It is CE-marked and now available in Europe.

ApertureCTC

Mark Packer has been involved with ApertureCTC – another thermal device. It’s similar to Zepto in many respects, but lacks the suction cup. It consists of a reusable handpiece and a disposable 1.2 mm diameter tip that houses a circular 5.25 mm filament, which can be deployed once the tip is in situ.

This is gently depressed on the capsule, a foot pedal is used to deliver a millisecond pulse of thermal energy, which melts the collagen and creates a perfectly round capsulotomy – and with it a smooth, strong and elastic capsular opening.

The manufacturers report that multiple filament dimensions are available, ranging from 4–6 mm.

Capsulotomy’s Evolution

The role of the capsulotomy has changed with cataract surgery over the last 270 years – from a crude opening to give access to the nucleus for its removal, through various iterations of cystitomes and forceps to create different shapes of opening for IOL support, to CCC for those anterior and posterior capsules to contain the IOL.

And now we have many devices from lasers to metallic thermal instruments to automate the creation of perfectly round consistent central capsulotomies – which should offer more effective lens position predictability.

Of course, IOLs have evolved with the capsulotomy, and a new generation of IOLs are being developed take advantage of this; for example, the Oculentis FEMTIS IOL with its small flaps – “rhexis clips” – that lock the lens inside the capsulotomy; or the Masket ND IOL (Morcher), which has a groove that fits inside the anterior capsulotomy. Could it be that the combination of these new, lower cost approaches to capsulotomy – plus a new generation of IOLs that rely on the properties of capsulotomies made by these devices – will soon consign manual CCCs to the history books too?