CATARACT SURGERY - What If The SARS-CoV-2 Is Present in the Anterior Chamber?

The Covid pandemic has profoundly changed the practice of ophthalmology. The availability of vaccines has greatly decreased the risk for infection in a large proportion of individuals in the United States, with 45.4% of the population having been fully vaccinated as of June 23, 2021.

Although we are gradually approaching a new normal, more than 50% of the US population remain at risk for infection, and it is still unclear to what extent fully vaccinated individuals spread the COVID-19 infection.

Reviewing the lessons we have learned to date about providing patient care during the pandemic will help ophthalmologists further adapt to a changed clinical and surgical landscape. Clinical practice for cataract surgery has already been dramatically altered by the pandemic.

Ophthalmologists are making decisions on a wide range of issues, including protocols for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), COVID-19 testing of sta, expectations regarding social distancing, and scheduling templates to accommodate new clinical protocols.

Although multiple vaccines are now available, a large percentage of the population (~55% as of June 24, 2021) have not been vaccinated. As a result, it is unlikely that ophthalmology practices will function in a pre-pandemic fashion in 2021.

The use of masks and the requirements for social distancing are expected to continue for quite some time.

ISSUES ENCOUNTERED IN RESUMING PRACTICE

The Office/Clinic As clinics and physicians’ offices reopen, all efforts should be focused, first and foremost, on managing the safety of patients and clinical sta.

Minimizing the use of waiting areas, reducing to the greatest extent possible the number of friends/family members who accompany patients, and enforcing the use of PPE for patients and sta all remain important.

Patient Selection

It is essential for eye care professionals to understand the limitations of SARS-Cov-2 testing and the subsequent implications for patient management.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has reported that reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests can remain positive for as long as 35 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and that it is unlikely for an individual to remain infectious for this extended period.

Deciding on how to manage individuals who have recovered from infection is also compounded by the fact that it is unclear whether the presence of neutralizing antibodies following a natural infection confers sufficient protection against reinfection.

It has been suggested that it is important to evaluate neutralizing antibody titers over time for both naturally infected and vaccinated individuals, in order to determine when they fall below a threshold associated with vulnerability to reinfection.

This interval and the threshold have yet to be determined. Ophthalmologists and their sta are also faced with a challenge when trying to identify those patients who most need medical treatment.

Some patients seeking to schedule appointments may not actually require immediate medical care and may be putting themselves and others in harm’s way.

Although the number of patients seen by ophthalmology practices has been dramatically reduced in recent months, the sta must still conduct screening procedures of prospective patients via telephone.

Prior to entering an office or a clinic, patients should be triaged to the latest possible date and all appointments reserved for those who are really in need of immediate medical care.

For example, a patient with rapidly progressing glaucoma migh be prioritized over a candidate for cataract surgery who sti has adequate vision.

Ophthalmology practices that manage patients with glaucoma and those in need of cataract surgery face an additional significant challenge: Many of these patients are elderly and thus at an increased risk for adverse outcomes following SARS-Cov-2 infection.

To address this challenge, ophthalmologists should consider scheduling follow-up visits at longer intervals and should try to conduct visits remotely whenever possible.

Telemedicine and teleophthalmology, in particular, had been used sparingly prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but have gained traction of late.

Recent findings from 2 studies—a retrospective chart review and a cross-sectional survey—have demonstrated that many patients are receptive to virtual office visits.

Performing Elective Surgeries

During the initial surge in COVID-19 cases, it was recommended that elective surgeries be postponed in an attempt to “flatten the curve” and not overwhelm the health care system.

In fact, visits and procedures for cataracts were reduced by 97% in March and April 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. Ophthalmologists have now returned to performing procedures, including cataract surgery, which is important for reducing the backlog of patients.

The pandemic has already resulted in a large surgical backlog of patients who were supposed to receive interventions during the US lockdown, along with those who are waiting for health care systems to ramp up again.

Circumstances that delay planned surgeries are particularly important for patients who are scheduled to undergo combined cataract and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, which has become common.

Delays in such surgeries are quite problematic because of the progressive damage and visual field loss in patients with glaucoma that is not eectively controlled with medications, as well as in those who lost access to their medications during the pandemic.

Patients’ conditions may be further complicated by referring physicians not yet having reopened their practices. For example, one patient was referred to our practice in March 2020 with high intraocular pressure but was not seen because the oce was closed.

Unfortunately, this patient was unaware of the urgency of his condition (and that treatment was available for him in an emergency setting). By the time our oce reopened, he had lost some vision.

During March and April 2020, an 88% reduction in inpatient and outpatient encounters for glaucoma was reported compared with the same period last year. It is reasonable to assume that some of these individuals required urgent care during this time.

Managing Patient Concerns and Behavior

Despite the fact that a large percentage of the population has been vaccinated against SARS-Cov-2, addressing patients’ fears surrounding COVID-19 remains critical. Even after vaccination, some people remain fearful of the infection.

A survey conducted by the American Psychological Association revealed that 48% of respondents who had been vaccinated still felt uneasy about resuming normal in-person interactions.

More educated patients may quite reasonably expect less crowding in the oce/clinic and waiting areas, shorter wait times, access to hand sanitizer and handwashing facilities, and consistent use of masks and face shields during medical examinations.

It has been noted that preemptively identifying patient concerns about in-oce visits, along with providing clear and concise information about the safeguards that are in place, can make patients feel more comfortable.

These messages are particularly important for those whose age or comorbidities may place them in a higher-risk category. It is encouraging to note, though, that the vaccination rate in older individuals in the United States is very high.

Information released by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) on June 1, 2021 indicated that 86% of individuals ≥65 years of age had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

It is important to note that the AAO continues to recommend that practices and clinics mandate social distancing in waiting rooms as well as the wearing of face coverings by both patients and caregivers.

Patients need continuing education about this requirement, particularly since masks may no longer be required in other settings and they may not understand the need to continue wearing a mask in health care settings.

Addressing Staff Issues

The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to affect office/ clinic staff in a number of different ways. For example, some staff may not want to return to work because they have added childcare responsibilities at home.

Some staff who want to return to work may no longer have a job available to them because of the practice’s lost revenue. Unfortunately, many practices are facing the possibility of bankruptcy or incurring tremendous debt, and staff reductions may be necessary for them to remain open.

The impact of the pandemic on ophthalmology practices is evident in a survey of AAO members in private practice (from April 9 to 13, 2020).

Survey results indicated that 89% of practices are applying for payroll protection through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and other resources.

In addition, a majority of respondents believed that without substantive federal grants and loans, their practices would be smaller, financially unhealthy, or both by the end of 2020: 47% will be smaller and financially unhealthy; 26% will return to pre-COVID-19 size and volume but will be financially unhealthy; 14% will be smaller but financially healthy; 6% will no longer practice ophthalmology; and 2% of practices will be sold.

All office and clinic personnel require training for their own protection as well as that of their patients. For obvious reasons, staff must be aware of COVID-19 symptoms and procedures for personal protection, including wearing masks, cleaning equipment, and using face shields.

Health care professionals, like anyone else, can deny illness and ignore symptoms. One might think that the need for attention to potential symptoms and personal protection would have diminished importance with the availability of vaccines, but this is not the case.

Results from a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of 1327 health care workers that was conducted from February 11 to March 7, 2021 indicated that only 52% had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

In addition, more than one-third of health care workers who had not received the vaccine indicated that they did not plan to be vaccinated.

Thus, a very important consideration for ophthalmology practices is the appropriate management of eye care professionals and staff who refuse to be vaccinated against SARS-Cov-2.

The American Medical Association has taken an appropriately strong position with respect to this issue:

“Physicians and other health care workers who decline to be immunized with a safe and eective vaccine, without a compelling medical reason, can pose an unnecessary medical risk to vulnerable patients or colleague.”

“When there’s a safe, eective vaccine to help prevent spread of a pandemic disease, physicians without a medical contraindication have an ethical duty to become immunized.”

“Physician practices and health care institutions have a further responsibility to limit patient and staexposure to individuals who are not immunized, which may include requiring unimmunized individuals to refrain from direct patient contact.”

Practical strategies for addressing this issue include education and identifying champions for vaccination among the peers of individuals with vaccination hesitancy. Education should debunk myths but also should acknowledge unknowns about vaccines (eg, long- term safety).

The ethical responsibility of health care professionals to become vaccinated should also be emphasized.

SURGERY

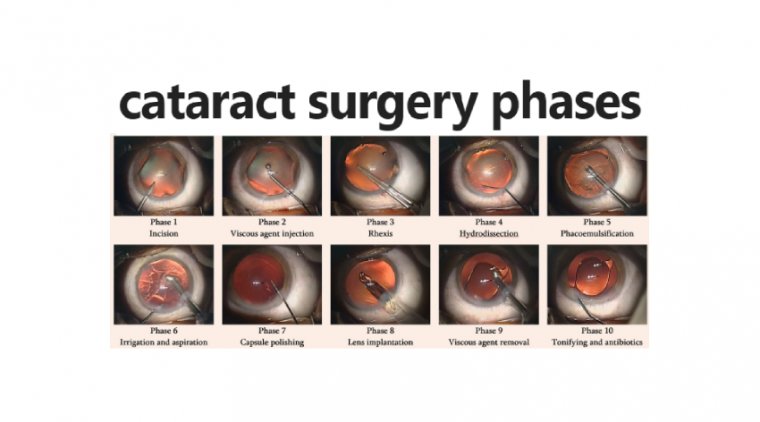

Planning surgery is iterative, with a number of tasks leading up to and beyond the procedure itself. This includes the preoperative visit, the actual surgery, and the postoperative care and management.

The AAO has also provided updated guidance with respect to these issues, which has remained largely unchanged from that published at the time when ophthalmology practices were just reopening.

Patient Screening

A careful screening process is an essential part of all medical practices, including ophthalmology. Patients should have their temperature taken upon arrival for surgery and should fill out a questionnaire about their health status.

Questions should include: Have you had a fever? Do you feel ill? Do you have a cough? This questionnaire can be modeled after other surveys used to identify patients with possible exposure to or symptoms of COVID-19.

Patients with symptoms or a history suggestive of COVID-19 should be referred for appropriate testing and notification should be sent to both infection control personnel at the health care facility and the relevant health departments.

It is also important to provide information about a patient’s COVID-19 status to other practices to which he or she may be referred. All health care practitioners have the responsibility to protect their colleagues to the maximum extent possible.

The challenge is that patients may not be aware of their own risk status. Guidance from the AAO states that in regions currently managing significant outbreaks of COVID-19, it is safest to assume that any patient could be infected and to proceed accordingly.

The SARS-CoV-2–positive Patient

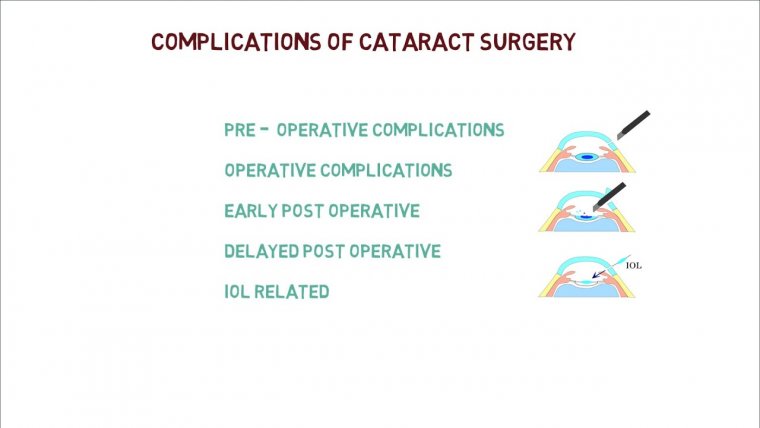

Performing surgery in a SARS-CoV-2–positive patient is highly problematic and should be avoided if at all possible.

Surgery in a patient with an active infection places everyone involved at risk and requires a tremendous amount of effort and resources to keep everyone involved safe during the procedure.

The challenge is in delaying the surgery for as long as possible in infected patients, but not for so long that it might result in adverse clinical outcomes.

Guidance from the AAO suggests that SARS-CoV-2–positive patients should quarantine at home, as specified by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, state public health authorities, or institutional guidelines.

Nonurgent treatment should be deferred until after quarantine and when a patient’s symptoms have resolved.

When surgery on an RT-PCR– positive patient is necessary because of the potential for permanent loss of vision or loss of life if delayed, the choice of anesthesia may be impacted by the patient’s overall medical condition.

The surgeon and operating room staff should wear N95 masks and eye protection and/or face shields.7 It may be appropriate for infected patients to be managed in a hospital or other setting that is equipped to provide both eye care and medical care to patients with COVID-19.

CATARACT SURGERY

The AAO has provided guidance on the use of surgical masks, eye protection, and face shields. Most importantly, every patient should be placed in a surgical mask during any ophthalmic procedure, in order to prevent asymptomatic transmission to the surgeon and the staff.

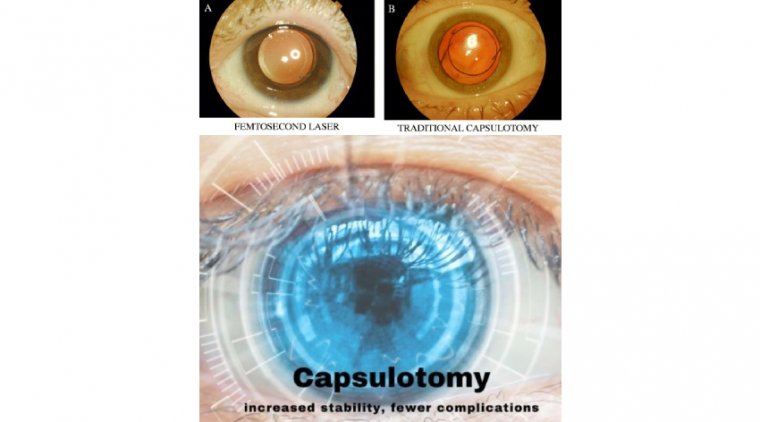

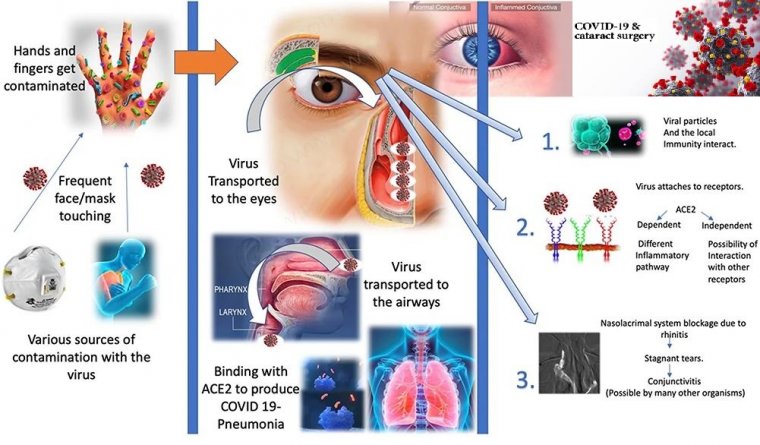

Concern has been raised regarding the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 via contact with the ocular mucosa, tears, or subsequent fomites, but it remains unknown whether infectious SARS-CoV-2 can be present in the anterior chamber.

Currently, little or no evidence exists to indicate that the eyes are a major reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 or a significant source of infection.

Results from a recent study of 72 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 revealed that 2 individuals reported conjunctivitis, with 1 of them testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 via RT-PCR evaluation of a sample obtained with a conjunctival swab.

It seems likely that this concern developed as a result of observations that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses the angiotensinconverting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptors present on human cells to bind to them and are primed to do so by the serine protease TMPRSS2.

Although ACE2 receptors are present in both the lung and the conjunctiva, the priming protease is not present in the conjunctiva; thus, it should not be possible for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to bind to the ocular surface and to initiate infection.

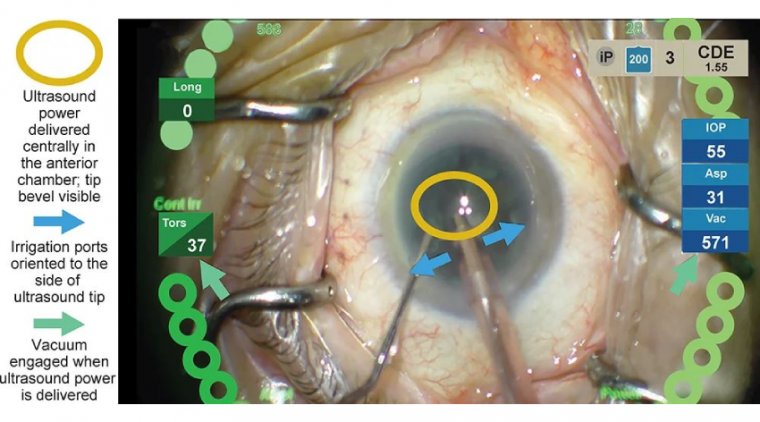

Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the use of phacoemulsification during cataract surgery will result in aerosolization of the virus, even if it is present.

Available data strongly support the view that droplets, rather than aerosols, are the main source of infection and that wearing a high-quality surgical mask provides protection against infection via this route.

All personnel should avoid touching their faces and should exercise hand hygiene by using an alcohol-based sanitizer product or handwashing with soap and water.

Postsurgical Management and Follow-up

Simplifying patient management following cataract surgery is important for minimizing the risk for infection. We cannot repeatedly bring elderly patients and those at high risk into the oce/clinic for follow-up visits.

The need exists to consider approaches to management that keep patients at home and safe.

Standard practice for prophylaxis against postoperative inflammation following cataract surgery has typically involved the application of perioperative eyedrops, such as those that contain corticosteroids.

The issue of eyedrop contamination is of particular concern in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath given the possibility that transmission may occur via contact with the conjunctiva.

Even before the pandemic began ,though, the limitations associated with the use of postoperative eyedrops for protection against inflammation had prompted interest in dropless approaches, such as those in which long-acting corticosteroid and antibiotic injectable formulations are administered at the conclusion of cataract surgery.

The postsurgical regimen can be simplified with the elimination of eyedrops. Not only do patients often have to go to the pharmacy to obtain their eyedrop prescriptions, but they also then forget to use them.

Utilization of a slowrelease intracameral corticosteroid eliminates the need for patients to use eyedrops after cataract surgery.

Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved DURYSTA™ (bimatoprost 10 mcg intracameral implant; Allergan Pharmaceuticals, Madison, NJ) for the treatment of glaucoma or ocular hypertension.

Placement of this implant can allow patients with glaucoma to go 4 to 6 months without applying eyedrops or visiting the pharmacy, which has helped me keep my patients treated and at home during the pandemic.

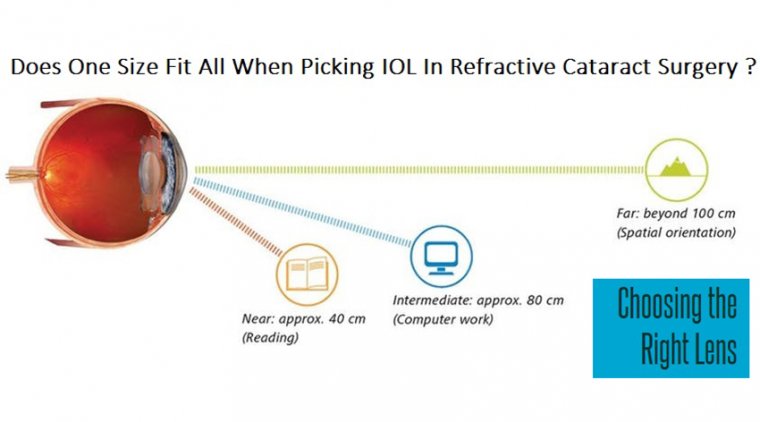

One novel corticosteroid that has been used effectively in dropless cataract surgery is dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9% (DEXYCU® ; EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Watertown, MA), which is a sustained-release formulation designed to be administered via injection into the inferior portion of the posterior segment at the conclusion of ocular surgery—most often, cataract extraction and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation.

More recently, dexamethasone intraocular suspension has been successfully administered directly into the capsular bag adjacent to the IOL.

Dexamethasone intraocular suspension has been shown to be safe and effective for treatment of the inflammation that occurs following cataract surgery and may be an alternative to corticosteroid drop instillation in this patient population.

It also has the potential to decrease the risk for infection that may be associated with the use of contaminated eyedrops as well as to reduce patient visits and associated complications, such as time spent in the waiting room and management of any individuals who may accompany patients to the clinic.

Other anti-inflammatory treatments that may circumvent the limitations of conventional topical anti-inflammatories have been recently approved by the FDA for use in patients undergoing cataract surgery.

Two topical formulations of loteprednol etabonate are now available: loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 1% (INVELTYS™; Kala Pharmaceuticals, Waltham, MA),42 which offers improved bioavailability via proprietary mucus-penetrating particle technology, and loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel 0.38% (LOTEMAX® SM; Bausch + Lomb, Bridgewater, NJ), which delivers a submicron particle size for faster drug dissolution in tears and greater penetration to the aqueous humor.

In addition, cataract surgeons now have the option of using the dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4 mg (DEXTENZA® ; Ocular Therapeutix, Bedford, MA)46—a dexamethasone-eluting punctal plug that provides tapered drug delivery to the ocular surface over a 30-day period, after which it dissolves and clears via the nasolacrimal system.

We have all been living through the COVID-19 pandemic for more than 18 months, and it is becoming clear that we will be dealing with this virus for some time to come.

Although there is bound to be frustration regarding the effects on our medical practices, we need to remember that our patients and colleagues are also dealing with a new normal that may be with us for several years.

We may have to slow down in our practices, but we should appreciate what we are doing for our patients and persevere in our efforts.