Cataract Surgery & Retinal Pathology

Understanding any structural abnormalities or pathology prior to cataract surgery is imperative.

Not all pathology is a contraindication to surgery, but it is critical to evaluate all findings to determine the patient’s visual potential with cataract surgery.

Must-know retinal pathologies include age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and clinically significant macular edema, epiretinal membranes and vitreomacular traction.

Subtle pathology can be impossible to detect during a fundus exam, viewing through a cataract; therefore, a good macula OCT exam is essential.

Other pathologies that can be identified using OCT include central serous retinopathy, macular edema, transparent epimacular membranes, vitreomacular schisis and early wet AMD with subretinal fluid, a small area of choroidal neovascularization and no hemorrhage.

Although it would be convenient if the patients we did our cataract surgery on had no other confounding variables to concern us, it is unfortunately the case that our patients often present with more than one problem.

A large percentage of the cataract patients that we see in our practice also have vitreoretinal issues to consider.

These issues may influence the decision on whether to do cataract surgery, the timing of the surgery, the technique used or the choice of implant. Often, we interact with retina colleagues in a team approach to deal with these patients’ multiple problems.

In some cases, the retina surgeons have referred the patient to our practice for treatment of a cataract that is limiting the retina specialist’s ability to visualize and treat the posterior segment.

But far more common are the many patients who come to us with cataract problems but are unaware that they have significant retina pathology.

It is our job to screen these patients for problems before we do their surgery, so that there are no “unhappy surprises.” One of our favorite axioms is that “the problem you find before surgery is the patient’s problem, but the one you find after surgery is your problem.”

Although some retina issues are obvious, others may be quite subtle and easily missed.

In our practice, we have found preoperative evaluation with SD-OCT to be an invaluable tool for screening cataract patients prior to premium IOL surgery and also for evaluating any patient’s macula that does not look completely normal on exam prior to any kind of anterior-segment surgery, such as cataract, lens exchange or corneal procedure.

We also use this technology to manage postoperative issues in patients who have recently had surgery or come in for second opinions because they are less than happy with the outcome of the surgery done elsewhere.

We’d like to discuss some clinical situations and present some cases that highlight the most common problems we deal with in our patients who have both cataracts and retina issues to consider. These cases are all taken from our own clinical practice and can serve as examples to facilitate discussion of specific issues.

Case 1: Severe Z Syndrome in High Myopia

In this interesting case, we determined the choice of treatment because of several concerns specific to the patient. Choosing the wrong approach could have created severe retinal issues, which we were eager to avoid.

This is a 50-year-old biomedical engineer who presented with bilateral Z syndrome after cataract surgery with Crystalens done elsewhere one year earlier. He is a very high myope with long, 29.8-mm eyes who received 6 D implants.

In both eyes, we saw severe fibrosis, posterior capsule haze and a Z syndrome with the lens pushed forward to the point that it was actually anterior the pupil plane on gonioscopy.

The Z syndrome had induced significant myopia and astigmatism and the capsular haze limited BCVA to 20/60 OD and 20/100 OS.

It was suggested by another surgeon that a YAG capsulotomy might relieve the Z syndrome, but we felt that there was no guarantee that this would be the case given the amount of fibrosis present and severity of the Z.

There was a large gap in each eye between the implant and the posterior capsule. We felt that there would be a high risk of vitreous prolapse with a YAG into this space, which would increase the risk of retina detachment and CME, while also complicating any future attempt to fix the Z surgically.

For this reason, we suggested to the patient that we do an IOL exchange, surgically reopen the capsular bag, remove the Crystalens and place a three-piece acrylic implant in the bag to be followed by YAG capsulotomy at a later date.

This procedure was done in the left eye first and the patient expressed great satisfaction with the outcome. His capsulotomy was done one month after his lens exchange and his vision is now 20/25 uncorrected in this eye. He is now eager to do the second eye.

Discussion of Case 1

In this case, we were well aware that we were dealing with a high myope, which did affect our decision-making process. But we caution that every patient must be evaluated on an individual basis.

We often see patients who are minimally myopic or even hyperopic who have very flat corneas and long eyes and thus are anatomic myopes. It is a good idea to check the axial length prior to your discussion of the risks and benefits of cataract surgery.

This is especially helpful when doing refractive lens exchange for a premium IOL because it is not uncommon to find a long eye in patients who are not necessarily highly myopic on refraction.

Sometimes, patients presenting with significant myopia have normal axial length but dense nuclear sclerosis or steep corneas causing the refractive changes.

We know that eyes greater than 26.0 mm in length are more prone to retina detachment after cataract surgery and that this risk is increased in patients who are younger, with some evidence of greater risk in males.

There is also much higher risk in the second eye of patients who have already had a retina detachment in the first eye with confounding data on the risk created by YAG capsulotomy.

It is our belief that when the implant is in the capsular bag and the posterior capsule is stretched against the posterior surface of the lens to tamponade the movement of vitreous forward after YAG capsulotomy, the risk is less than if there is a gap or space that allows vitreous to herniate through the opening and thus create vitreoretinal traction.

For that reason, in this case we preferred to create a situation where the implant would be secure in the bag against the posterior capsule prior to doing a capsulotomy, with the goal of reducing the risk of vitreous herniation.

Another issue that affects high myopes is myopic macular degeneration. It is important to bear in mind that many high myopes will develop macular atrophy and subretinal neovascularization as they get older.

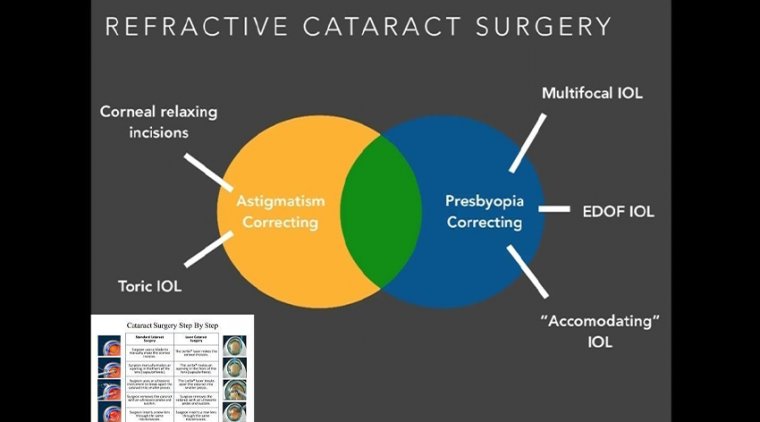

For this reason, we are reluctant to use multifocal implants in patients with very long eyes.

We think it’s a good idea to do something akin to an “actuarial analysis” of patient lifetime risk for macular disease when you consider putting a multi-focal implant in a younger patient who is either a high myope, is diabetic, has early RPE changes or has a strong family history of AMD or early epiretinal membrane.

The risk is that these problems may progress to the point that the implant they paid extra for is now doing them more harm than good.

Case 2: Discovering a Hidden Retina Problem

This is a patient referred by another ophthalmologist for cataract and glaucoma surgery. She is a 62-year-old with one eye (the other eye was lost years ago to trauma) with 20/60 vision, a dense cataract and a pupil that does not dilate because she is on pilocarpine (as well as other topical glaucoma medications) in part because she has a narrow angle and has not yet had an iridotomy. Her IOP was 24 on maximum medication.

Although we could not see her retina clearly, we were able to obtain an excellent image with the SD-OCT through the cataract that demonstrated fluid in the macula from a peripapillary disciform lesion.

In this case, prior to performing cataract surgery we referred her to a retina colleague who did an anti-VEGF injection and laser treatment of this leaking area, resolving the problem completely. She then underwent successful cataract/glaucoma surgery with a 20/20 visual outcome.

Discussion of Case 2

We like this case because it demonstrates the ability of the SD-OCT to pick up things that sometimes can’t be seen at all on examination.

Our view of the retina was compromised by a small pupil and cataract. Although we did not see anything that would have prevented me from going forward with cataract/glaucoma surgery, we were fortunate that we were able to initially evaluate this patient with SD-OCT so that this problem could be discovered and treated before I operated on her.

We now consider peripapillary subretinal neovascularization (PPSRN) a fairly common entity in our patient population, whereas before having OCT in our practice it was something we rarely diagnosed… no doubt because it was just not on the radar screen and very difficult to see.

Most cases of PPSRN are associated with AMD but it can be idiopathic or associated with inflammatory choroiditis, angioid streaks, disc drusen, histoplasmosis, choroidal osteomas and other pathology. PPSRN can be treated with focal laser or anti-VEGF medication.

Subretinal neovascularization (SRN) from AMD or choroidal nevi may be quite subtle and completely missed on exam, as in the case of a bilateral toric implant patient who felt that the vision in the left eye was slightly worse than the vision in the right (20/30 vs. 20/20). He had a choroidal nevus associated with SRN causing serous elevation of the macula in the left eye.

Case 3: One Eye Shorter Than the Other, or Is It?

This is a 78-year-old gentlemen who was referred by an optometrist for cataracts in both eyes. His vision was 20/100 in the right eye and counting fingers in the left. His auto refraction was +1.0 OD and +7.0 OS and he had no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD).

When we measured his axial length, the left eye was 2 mm shorter than the right. He had about 2+ nuclear sclerosis. I did not feel these changes were consistent with his visual deficit, particularly in the left eye.

When we examined his retina, the appearance looked essentially normal but our view of the left eye was obscured by severe asteroid hyalosis.

We told this patient that he likely never had good vision in the left eye because of amblyopia (which we assumed), given the difference in refraction and axial length between the two eyes, as well as the visual loss out of proportion to cataract changes there.

The patient assured us that he saw perfectly out of the left eye as recently as a year ago. We decided to attempt an OCT evaluation, which revealed a lamellar macular hole in the right eye and a severe vitreomacular traction syndrome in the left eye.

The patient was referred for vitreo-retinal surgery in the left eye, which was performed successfully, and cataract surgery followed in both eyes, leading to 20/30 vision in the OD and 20/50 in the OS.

Discussion of Case 3

This is another case that demonstrates the ability of SD-OCT to see the things that can’t be discovered on clinical exam alone. It also highlights the spectrum of vitreomacular interface abnormalities that are extremely common in clinical practice but rarely diagnosed prior to OCT.

We see vitreomacular traction syndromes in patients presenting with decreased vision before and after cataract surgery.

The spectrum of vision loss — from slight deficit to profound loss — with minimal or no obvious pathology on examination is impressive.

A related example is a patient who was referred with bilateral cataracts and had vitreomacular traction in both eyes. In that case, we decided to move forward with cataract surgery first and then do retina surgery if necessary.

The patient ended up 20/25 in both eyes and was quite happy with his vision, so no vitreoretinal intervention was necessary.

Another related example is a patient who had a more severe vitreomacular interface abnormality with a thickened posterior hyloid and with vision decreased to 20/70. This patient came to us one year after cataract surgery after an initial excellent outcome. She was referred for vitrectomy.

Often the vitreomacular interface abnormality pulls off on its own, leading to a lamellar hole of varying severity. The lamellar hole may be associated with a mild loss of BCVA and a microscotoma. In some cases, the patient may be completely asymptomatic.

Next is an example of a patient referred by an optometrist. We did a Crystalens in the first eye and, although she was ecstatic with her vision, we were not happy because we could not get her to see better than 20/25-1, nor did she read as well as we would have liked.

When we did the SD-OCT, we saw that she had a lamellar hole in both eyes. Because she was happy with the first eye, we went ahead and did Crystalens surgery in the second eye with the understanding that her vision would be likely be limited to 20/25. She ended up very happy with this outcome.

Lamellar holes are extremely common and, we believe, underdiagnosed. We have seen many patients who have come in for a second opinion, because they are unhappy with the outcome of their cataract surgery, and have lamellar holes to blame.

We believe that the presence of vitreomacular interface abnormalities and lamellar holes may create a contraindication to multifocal implants in most of these cases and can only be effectively recognized and diagnosed with OCT.

For this reason (among others), we screen our premium implant patients with OCT prior to final IOL recommendation.

Case 4: Cataract Surgery and Epiretinal Membrane

This is a 60-year-old who was told she needed cataract surgery in the left eye and came in for a second opinion. She had a significant epiretinal membrane associated with moderate cataract changes and 20/100 vision best corrected.

The other eye was 20/25+2 best corrected with −6.0. She was a contact lens wearer.

A decision was made to do a combined procedure, cataract surgery with pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peeling, largely influenced by the patient’s strong desire to “take care of everything at once.” She ended up with an excellent anatomic and visual outcome of 20/20 and −0.5 refraction in this eye.

Discussion of Case 4

This case opens up the discussion of ERMs and how they influence the decision-making process in cataract surgery.

It is really impossible to know the effect that an ERM has on the macular anatomy without OCT. Even with the images the SD-OCT provides, it can be difficult to correlate the macula changes with visual symptoms accurately.

Sometimes we see an ERM that looks impressive but the macular anatomy is absolutely normal and we can move forward with cataract surgery with confidence, as in this patient who had Crystalens surgery and a 20/20 outcome now stable three years postoperative.

Case 5: Cataract Hindered Retina Treatment

This is a 60-year-old patient referred by a retina colleague for cataract surgery. Although the patient has had macular laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy in the past, the retina specialist’s ability to continue to treat was severely compromised by a very significant cataract that made it quite difficult to view the retina details.

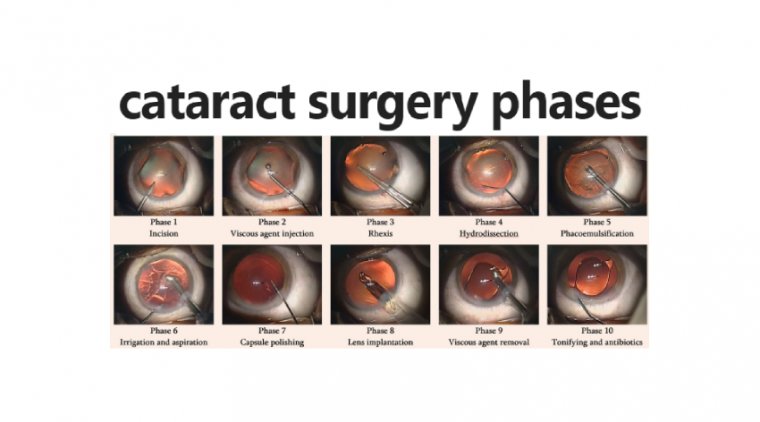

After we obtained the OCT image, we decided to move forward with cataract surgery combined with a pars plana triamcinolone injection and then followed up with more laser treatment a few weeks after surgery.

Discussion of Case 5

While a full discussion of cataract surgery in the face of diabetic retinopathy is beyond the scope of this article, we feel the following points are worth considering.

Treating the retinal issue maximally prior to surgery is ideal, but it is not always possible to completely eliminate macula edema.

We have found that combining cataract surgery with an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone at the time of surgery prevents the macula from getting worse as a result of the surgery and often leads to significant reduction of macular edema in the postoperative period.

In some borderline situations where there is diabetic macula edema, cataract and glaucoma in a patient who is a steroid responder, we may combine the cataract surgery with glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy, ExPress mini shunt or a tube shunt) and a triamcinolone injection.

In other cases, we may consider the use of Avastin rather than triamcinolone. We do an SD-OCT evaluation of all diabetics with retinopathy prior to cataract surgery, and if there is either clinically significant macula edema or even a borderline situation, we prefer to treat aggressively prior to surgery with argon macula laser treatment and supplement with intravitreal triamcinolone at the time of surgery if indicated.

A Varied Range of Challenges

The cases reviewed here are representative of the broad range of challenges that can confront a busy cataract surgeon.

These cases should also make clear the high value I place on OCT as a key diagnostic tool in a cataract practice. In addition, the cases emphasize the critical importance of working closely with retina colleagues in the management of patients whose cataract surgery is made complicated by retinal issues. The team concept can be invaluable in bringing these cases to a successful outcome.