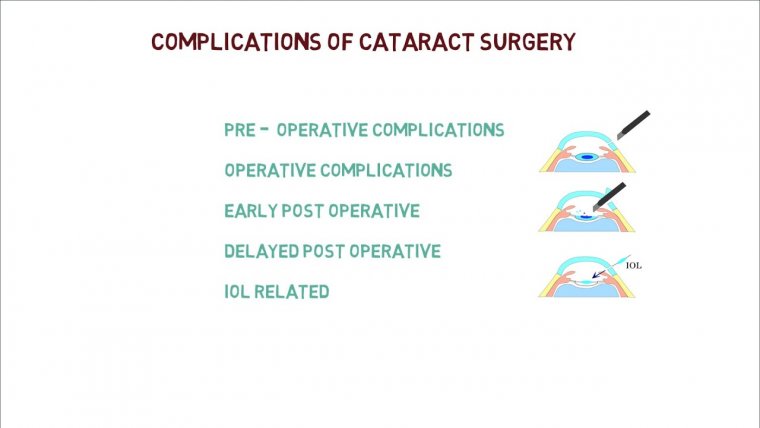

Complications Of Cataract Surgery

Cataract surgery dates back to the 1700s. With new advancements in technology, infectious disease control, and equipment, there are fewer postoperative adverse events following the procedure.

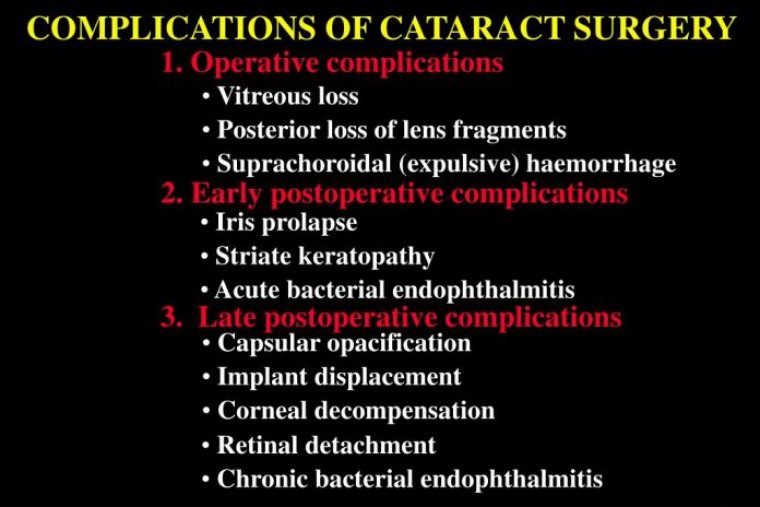

However, complications still do occur both intra and post-operatively. The current goal of cataract surgery is to remove the cataract and replace it with an intraocular lens, which is typically placed in the capsular bag of the posterior chamber.

As with any surgical procedure there are risks associated with operation and the post-operative state.

There are complex cases that any cataract surgeon might encounter at the operating table, and here are a few thoughts on how they could be handled.

Visibility

There are certain conditions that can meaningfully obscure the view at the microscope compared to the slit lamp. When a patient is lying flat, the diffuse lighting of a microscope can make corneal opacity, haze, or other pathology more visible.

To get the best possible view, it is essential to adjust focus and coaxial lighting; decreasing oblique light may also help. Fortunately, newer microscopes limit the need for adjustment – in particular, those with red reflex technology. In some cases, however, we need more than the latest tech.

A patient with a vitreous hemorrhage, for example, lacks red reflex and visibility under the scope is still poor. In those cases, we use a cell stain (trypan blue) during anterior capsulotomy.

If a surgeon thinks they might need a stain, we recommend that you use it without hesitating. The only caveat is if the patient also has loose zonules; the stain could go to the back of the eye if it’s overused (a problem that can be avoided by using a little disperse viscoelastic at the peripheral sulcus space).

Another option when visibility is poor is to use a fragmentation technique that limits the need for a red reflex. One option is the use of microinterventional lens fragmentation device (miLoop).

Even in eyes with dense vitreous heme or no red reflex, it still allows us to see the metallic reflex of the lens fragmentation device as it breaks the lens into four to six quadrants before phaco.

Density

In the past, dense lenses were not always considered for extracapsular extraction, but thanks to newer phaco platforms, almost any cataract can be broken up using ultrasound technology.

Optimization of the density settings is key for fragmentation efficiency with modern platforms; even with the best technology, some cases require a lot of energy to break the lens pieces. In addition, very dense cataracts often have a fibrotic leathery plate that is nearly impossible to crack using standard techniques.

Femtosecond lasers can assist in these cases, although the settings may need to be changed to allow for penetration of the deep plate.

The MiLoop can be used to fragment dense lenses as well. Ultimately, we have options available to us when working with dense lenses, which should allow us to adequately fragment without causing complications, such as a wound burn or posterior capsular tear.

Zonulopathy

Zonulopathy can be both pre-existing or iatrogenic. Risk factors include trauma, pseudoexfoliation, genetic syndromes, high myopia, and dense lenses.

Any prior act of anterior chamber shallowing, such as surgery, vitrectomy, intravitreal injections, or angle closure could also cause zonules to weaken. Although phacodonesis is often visible at the slit lamp, some cases are not apparent until surgery has begun.

Certain techniques can help prevent further weakening of the zonules, even when discovered at the operating table. A chopping technique can help the surgeon adopt an outside-to-in motion instead of the inside-to-out motion used during the divide-and-conquer technique that could exacerbate weakness.

Lowering the bottle height or intraocular pressure of the phaco machine can also avoid over-deepening of the chamber. In addition, using gentle, slow maneuvers is key – so is having tools, such as capsular retractors, to help prevent the lens from falling back.

One consideration is to flip the lens out of the bag if it appears to be falling posterior, and working anterior to the iris plane, taking care to avoid endothelial damage.

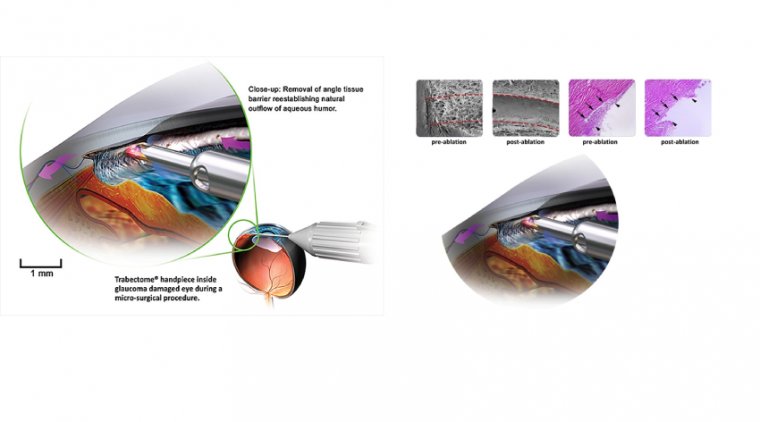

After phaco, it is necessary to address the loose zonules. We would recommend familiarity of sizes and types of capsular tension rings (CTR). The rings are made in several sizes that are dependent on white-to-white to axial length, and their placement redistributes the applied force to the entire circumference of the bag by stretching it taught.

The goal is to place the CTR as early as you need to but as late as possible as once placed, removal of the nucleus and cortical material might be more difficult. For zonule loss more than 3 clock hours, a CT segment may need to be used.

Inexperience

There are many articles in peer-reviewed literature about the cataract surgery learning curve.

Though surgical complications can occur under the care of any surgeon, the rate substantially reduces as experience expands; one study showed a nearly 50 percent decrease in the rate of posterior capsule tear and/or vitreous loss after the first 60 cases, while another has suggested an improvement after 60–90 cases.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has set 80–100 cases as the minimum requirement for cataract surgery to graduate from residency. At that rate, not only do complication rates decrease, but surgeons’ operative time continues to decrease as well.

Tears

Anterior capsule tears are rare but they can happen during surgery. One tactic to minimize occurrence is effective patient sedation; unsurprisingly, movement during a capsulotomy increases the chances of a tear.

There are cases when an intumescent lens could also bring about a tear because of the added pressure that it exerts within the capsular bag.

If we encountered this complication, we would decompress with a needle, use a heavy viscoelastic, and begin with a smaller capsulotomy than usual to avoid an enlargement of the capsulotomy in the middle.

Posterior capsule tears can also occur at any time during nuclear fragmentation, but there are three points during surgery when we have most observed residents encounter these issues.

The first is during the groove in a divide and conquer case; grooving too deeply (especially on the part of the lens 180 degrees from the wound) can create a posterior tear while to shallow can create an anterior capsule tear.

The second is when the surgeon is removing the first lens piece. If the phaco emuslifies the piece rather than move it out of the bag, the posterior capsule is vulnerable. Understanding the phaco machine and whether it is peristaltic- or vacuum-based as well as how to efficiently capture pieces is key to preventing this error.

The third is when the surgeon is emulsifying the last piece, which is to say when there is no nucleus to protect the posterior capsule from the phaco handpiece. Keeping the chamber formed without shallowing and avoiding surge can help avoid this complication.

If a posterior capsule tear does occur, a surgeon’s first instinct should be to go to foot position 1 (irrigation only) and then insert a dispersive viscoelastic without shallowing the chamber.

The ability to keep the eye inflated with the dominant hand, while inserting the viscoelastic with the non-dominant hand is not always easy. We encourage trainees to practice the maneuver early on. Once the chamber is filled, the phaco handpiece can be removed and a decision made on the next steps.

Zonulopathy

Iatrogenic zonulopathy can occur at any stage of surgery. Applying too much pressure during lens fragmentation is a common cause among residents; mastering the positioning of instruments is key to avoiding this complication.

If there is an area of zonular dehiscence, it is also important to employ techniques that can avoid enlarging or further weakening the area. Finally, if there is an area of zonule weakness, it helps to use a dispersive to push back the equator to avoid further complications.

From our experience, zonular damage occurs most frequently during cortical removal. It is often created by moving the aspiration handpiece too peripherally, where there is very little cortical material, and quickly trying to aspirate.

A type of “snap back” of the material can sometimes be seen in these situations; instead of cortical material flowing into the aspirator, the equator resists the movement. Once an area of zonule weakness is identified, it helps to limit the amount of vacuum and to remove cortical material in a different area.

Changing to a bimanual setting can be helpful. When it comes to addressing the area of weakness, gentle movement toward the area of weakness is best.

In accordance with the Miyake-Apple technique, the best way to limit zonule dehiscence is to go tangential to the equator rather than pulling perpendicular and centrally.

Alert Discreetly

The most important resource that a surgeon has is their team; in cases of complications, you must find a way to discreetly alert them that the surgical plan has changed, so that they are all aware and ready to assist – all without alarming the patient.

If the patient is relaxed and under anesthesia, the surgeon can get through the case without the patient ever knowing there was a complication until it is explained postoperatively. Sometimes it helps to have a code word.

For example, when we calmly say, “let’s open the vitrector,” the whole operating room understands that there’s a complication and everyone – from anesthesia (more sedation, including topical, may be required), to the circulator, to the scrub nurse – is aware and ready to respond.

Tools At The Ready

Surgeons must ensure that they have all tools at their disposal to manage complications ahead of every surgery. When complications happen, they happen quickly and the whole operating team needs to be equipped to respond.

Understanding the set-up, how the machines operate, and how to troubleshoot are all very important.

It is also important to have all lens options and formulae available, even during a routine case. Understanding the lenses – and how to load them – is essential.

Plan for the worst, do your best

The second a complication occurs – whether surgeon-induced or somewhat anticipated – there is a moment of surgeon stress. The key is to have a plan, to manage complications calmly, efficiently using the tools at your disposal.

No surgeon wants to encounter complications, but they occur even in the most experienced of hands. Addressing pre-existing conditions, being aware of common surgical pitfalls, and knowing how to manage anything you might encounter will all help ensure a successful outcome for your patients.