Keratoconus & PMD Patient With Cataract

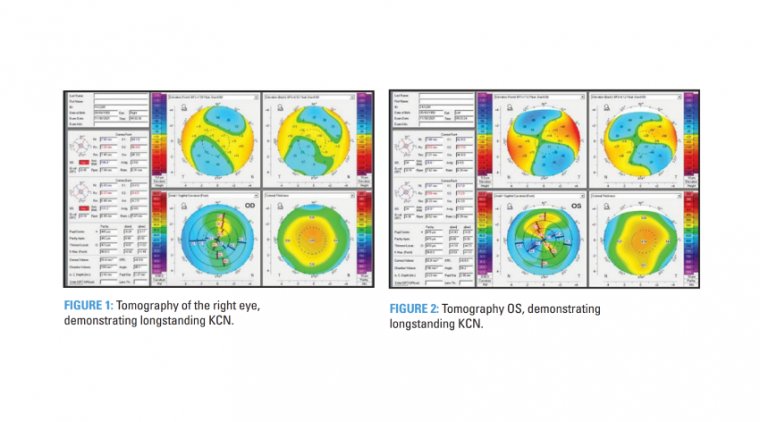

Keratoconus (KCN) is a condition of the cornea typically resulting in asymmetric thinning and steepening of the cornea, often leading to irregular astigmatism and resultant decreased visual acuity.

It is often associated with eye rubbing, atopy, and asthma. While the condition can be diagnosed at any age, it typically presents in adolescents and young adults and can now be stabilized with CXL.

To achieve best-corrected visual acuity, glasses or specialty contact lenses are often required. The prevalence of KCN is approximately 1 in 375 people, although this number could be higher than reported.

Approaching cataract surgery in patients who have a history of keratoectasia, including keratoconus (KCN) or pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD) requires careful assessment of corneal stability, keratometric values, IOL selection, and surgical technique to increase the likelihood of a successful outcome.

Corneal Stability

Corneal cross-linking (CXL) prior to cataract surgery should be considered on a case-by-case basis depending on the stage of the cataract and the progression or stability of the ectatic corneal condition.

If the patient’s KCN has been stable, longstanding, or even undiagnosed, for example in older patients with no signs of progression and a visually significant cataract, cataract surgery is likely warranted for optimal and timely visual rehabilitation.

After cataract surgery, monitoring the cornea for disease progression that would warrant CXL is reasonable. Because keratometry values and, therefore, biometry values can fluctuate after CXL, and may ultimately take up to several months to stabilize after CXL, cataract extraction is warranted primarily for prompt visual rehabilitation.

CXL, however, can be performed to stabilize the cornea first while observing the cataract if the cataract is not visually significant — especially in documented progressive KCN in a younger patient who has mild cataracts.

Contact lens over-refractions can be useful in these situations to determine how much the cataract is contributing to the patient’s visual compromise.

Topography-guided PRK could be considered on a caseby-case basis to improve the regularity of the cornea months or years prior to cataract surgery at the time of or after CXL if the cataract is not visually significant.

Finally, if the patient requires a keratoplasty, this may need to be performed prior to cataract surgery, if possible, to allow for a more accurate refractive result.

Keratometric Values

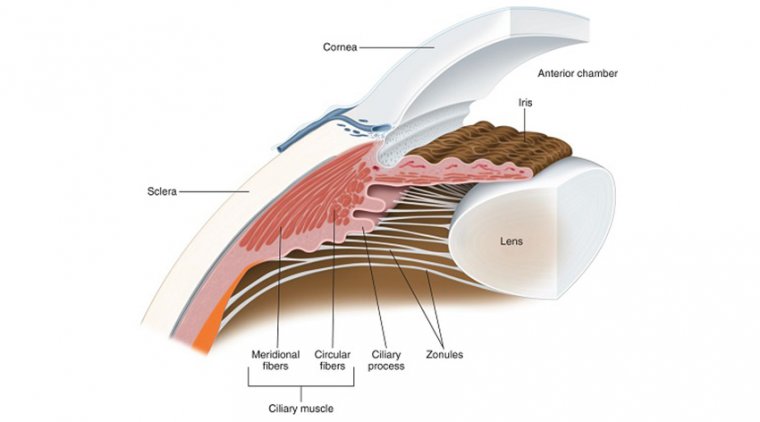

Due to the irregular nature of the cornea, specifically in the central 3 mm to 4 mm zone where biometry measurements are taken, reliable measurements are more difficult to obtain in KCN patients.

Also, coexisting conditions, such as dry eye disease, which we know affects the tear film, can alter the effective IOL position and measurements compared to a normal eye.

Additionally, the visual axis in KCN patients may not be located in the cornea’s steepest location, influencing the impact of the IOL’s effective position on refractive outcome.

Therefore, the location of the cone, whether more central or peripheral to the visual axis, has a critical effect on the IOL calculation and final refractive outcome.

The more centrally located the cone and degree of irregularity, the greater the impact and the reduced predictability of the IOL calculation.

The keratometric index of refraction of 1.3375 overestimates the corneal power and underestimates IOL power in KCN eyes, leading to a hyperopic surprise.

While using the total corneal power can improve outcomes, there is no consensus as to where on the cornea this measurement should be taken. One consideration is that since the corneal apex is decentered in KCN, the keratometry (K) readings should be done over the central cornea.

The good news: Using biometric Ks and adjusting the aim for a low myopic refraction tends to improve the refractive results in mild-to-moderate KCN.

An added benefit of a myopic target refraction is increased near vision without contact lens or spectacle correction. Additionally, a myopic target refraction facilitates scleral lens wear due to its optics. Specifically, the precorneal tear fluid reservoir acts as a high minus lens up to -15 D.

If a hyperopic surprise were to occur, scleral contact lenses correcting hyperopic prescriptions have greater central thickness and a smaller front optical zone diameter. This has the potential to induce higher-order aberrations and reduce visual quality.

So the question becomes, “how much myopia should be targeted when choosing the IOL power?” This is a challenge and somewhat of an art form required by the surgeon when treating these eyes.

Typically, the higher keratometry values and the more advanced the KCN, the greater the chance of a hyperopic surprise, so an increased adjustment should be made.

Ghiasian et al proposed certain refractive targets based on K values: If K readings are less than 47 D, a post-operative refractive target of -1.00 D can be used, in conjunction with the Holladay II or Hoffer Q formulas.

If the K readings are between 47 D to 50 D, the SRK/T formula can be used with a target refraction of -1.50 D For eyes that have higher K powers, using a standard K value of 43.25 and a target refraction of -1.80 D has yielded good outcomes, as no single formula has demonstrated consistent accuracy.

Another way to achieve accurate K values in KCN patients is to prescribe a significant contact lens holiday, keeping in mind that many of these patients have worn rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses for years or decades, which can affect measurements.

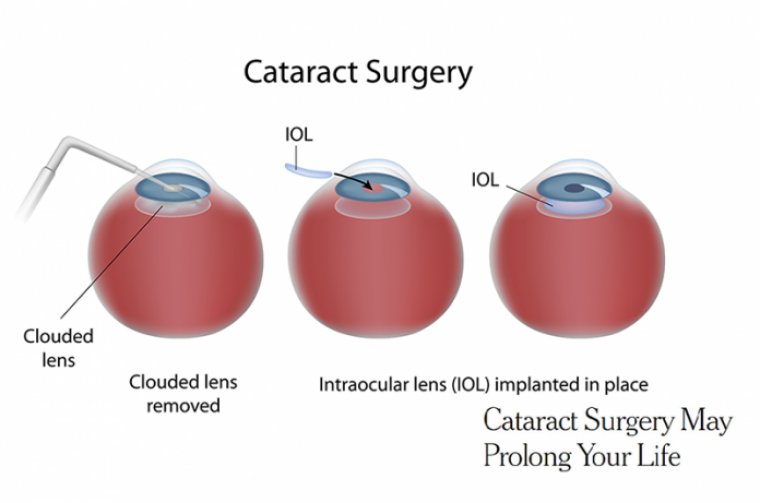

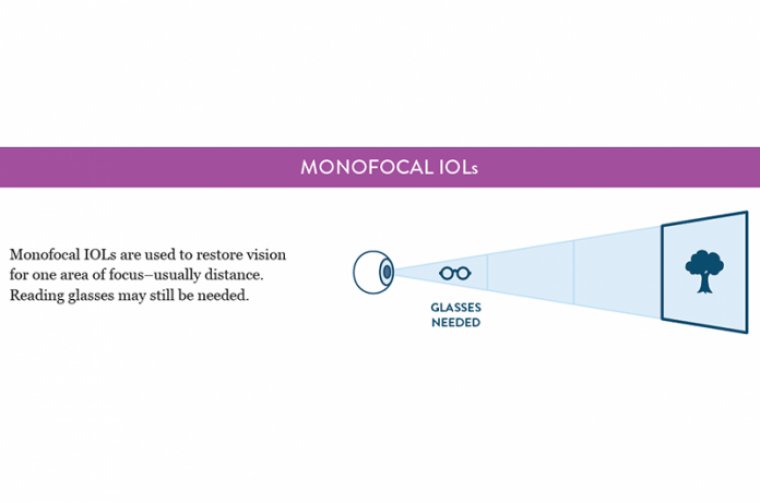

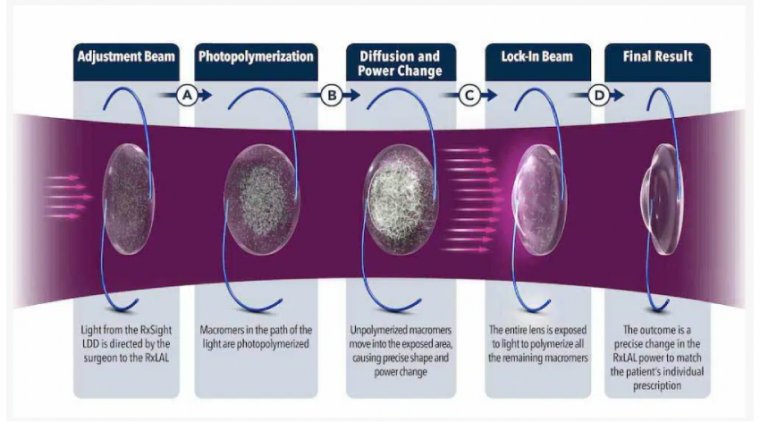

It is often suggested that patients cease lens wear for approximately 1 week per decade of lens wear time prior to measurements. IOL Selection Patients who have KCN can be candidates for toric or monofocal IOLs. We do not typically use multifocal IOLs for these patients.

• Monofocal Toric IOLs. Consideration of a toric IOL is possible in mild-to-moderate KCN, specifically in cases of mild irregular astigmatism that have lower orders of aberrations and good best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) with spectacles.

It is critical to use corneal topography and tomography when making this decision. Evaluating the central 3 mm to 4 mm zone for a consistent axis of astigmatism among the testing modalities, in addition to checking for minimal skewing in this region, could help a surgeon make this decision.

Patients in whom risk of progression is minimal with topographic stability for a year and improvement with refraction can be candidates. Typically, eyes that require hard lenses to achieve BCVA with no clear axis of astigmatism are not good candidates for a toric IOL.

It also should be considered that if the patient plans to use their RGP or custom lens after the surgery and a toric IOL is present, the lens will then unmask the internal astigmatism from the IOL.

In patients who have large axial lengths (> 25 mm) and white to whites (> 12.5 mm), there is an increased risk of toric IOL rotation postoperatively, which could be attributed to the thinner optic profile in lower-powered IOLs occupying less volume in the capsular bag.

Placement of a capsular tension ring may be used to prevent rotation if the decision is made to pursue a toric IOL in these patients.

• Monofocal non-toric IOLs. These are always acceptable but may be deemed particularly appropriate in cases in which the astigmatism may not be able to be corrected due to its irregular nature.

In this case, ongoing use of a RGP lens postoperatively may be needed to optimize vision. In severe KCN cases, the magnitude of irregular astigmatism is too large and can affect postoperative spherical equivalent and visual acuity.

Finally, the sphericity of the cornea should be assessed in relation to the IOL being considered, as this can influence refractive outcome: Many keratoconics have a large negative Q value due to their steepness and asphericity, so placing an IOL with a Q value of 0 or positive value may provide improved outcomes.

Using aspheric IOLs reduces the effect of corneal asphericity on postoperative refraction. For each 0.1 difference of Q value, the prediction error is lower with an aspherical IOL compared to a spherical IOL.

Surgical Technique

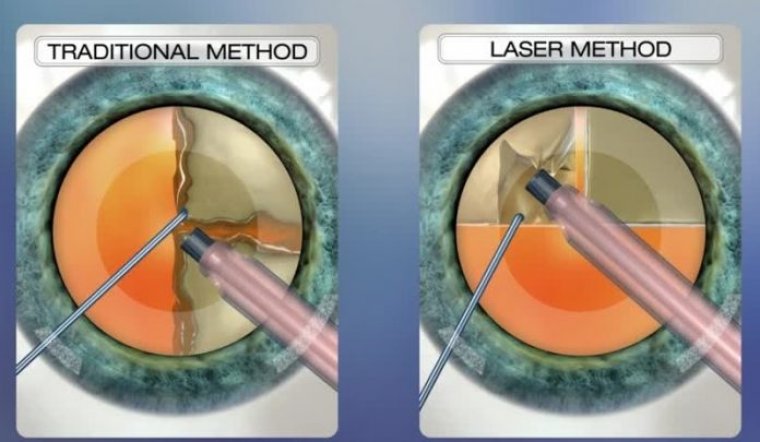

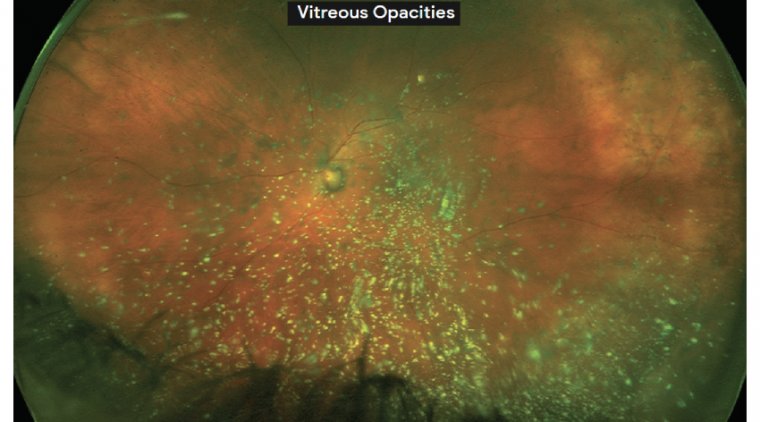

In the presence of diffuse scars intraoperatively, the view under the surgical microscope is worse than at the slitlamp due to the microscope’s central diffuse light. This causes light scattering with shadows and reflections, decreasing visibility and increasing distortion.

To mitigate this, one can place dispersive viscoelastic on the cornea to hydrate the epithelium while making the corneal surface more regular and mildly magnifying the view for key steps.

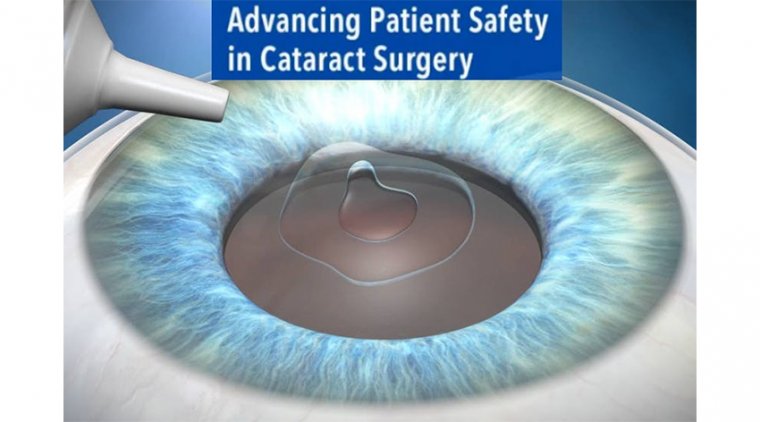

Use of capsular staining dye is also recommended during creation of the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, even in cases where there is a good red reflex. Some have also suggested using a RGP contact lens during the procedure to improve visibility during the procedure.

Options to manage cataract surgery wounds in KCN patients include placing a nylon suture in the main wound or constructing a scleral tunnel incision. The reasons: Wound construction can be complicated by progressive ectasia, and creation of a self-sealing clear corneal incision may not be possible.

If creating a clear corneal wound, placement at the limbus is critical, given how thin keratoconic corneas can be.

Additionally, some advocate for giving attention to the peripheral corneal thickness rather than the astigmatism axis when choosing the location to create the main incision in order to ensure that there is adequate corneal tissue to create a stable wound.

Finally, reducing IOP during phacoemulsification is recommended to reduce stress on the cornea.

A Multifaceted Approach

Cataract surgery in patients with KCN requires a multifaceted approach with attention to severity of KCN, preoperative measurements, and anticipated postoperative outcomes.

Additional precision is required during surgery, with special attention to wound construction and maneuvers to improve visibility and reduce distortion, allowing for safe phacoemulsification. With careful assessment of these parameters, patients can have good outcomes.