Evolution of Cataract Surgery

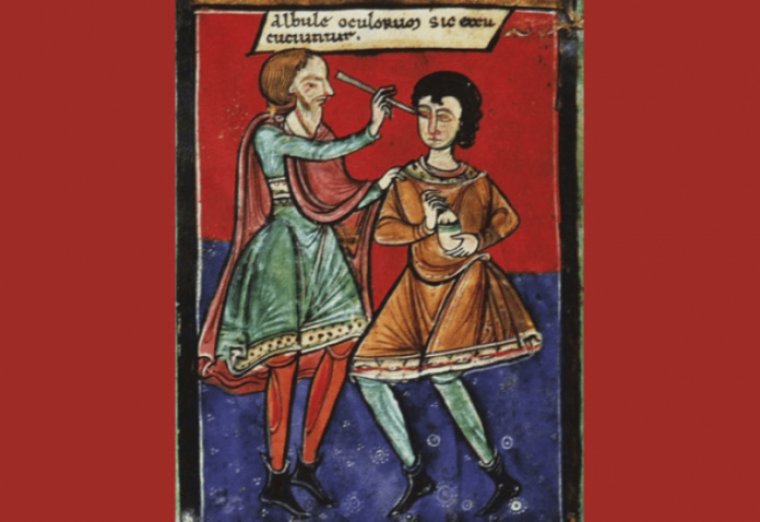

Cataract surgery is one of the most common procedures performed worldwide. It is also one of the oldest. The earliest known method of treating a cataract is couching, which dates back to the fifth century BC.

The word “couching” comes from the French verb “coucher,” which means “to put to bed.” Couching was typically performed on mature cataracts. The cataract was not removed from the eye.

Instead, the mature cataract was purposefully dislodged out of the visual axis with a needle. The cataract remained in the eye but was no longer blocking light, producing instantaneous improvement in vision.

Cataract surgery, as we know it today, has become a fairly simple procedure for patients that often requires less than 15 minutes and minimal recovery time. But, like most other surgeries, it hasn’t always been this way.

Not until the last 20 or 30 years have we reached this advanced state in which patients can have their surgery done in mere minutes and leave seeing very well at distance without glasses, which is really incredible. It’s something that we all take for granted now.

At first, we doctors were just learning to do it well and trying to get the best results for our patients. But later we thought to ourselves, ‘How did we get here?’ We were very curious about these techniques and figured the story of their invention might be interesting. Then, we found the stories were way more compelling than we ever imagined they could be.”

Early Treatment Methods

From about 800 B.C., when couching was first performed in India, and for centuries later, cataract patients faced a treatment method that now seems barbaric.

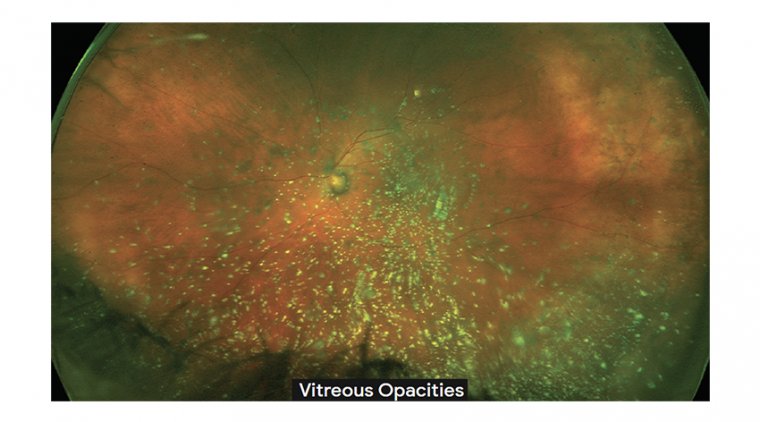

“The practitioner would sit facing the patient and pass a long needle through the cornea to impale the lens. “He would then forcibly dislodge the lens — rupturing the zonules — and push it into the vitreous cavity, where it would hopefully float to the bottom of the eye and out of the visual axis.”

As unpleasant as it sounds, couching was the preferred method of handling cataracts — of course, it was the only method.

People took this option when they were almost blind from mature, opaque cataracts. Only then did the benefit of the procedure outweigh the risk.

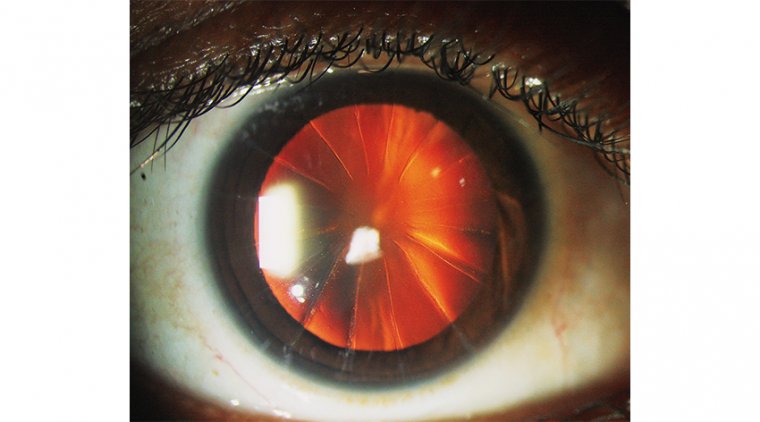

In the early 20th century, the treatment evolved to intracapsular cataract extraction. With this method, a surgeon made a large semi-circular incision around the cornea at the limbus and reached inside the eye to remove the lens with forceps.

However, this method presented two downsides. First, a long healing time required the patient to lie on his or her back in a hospital for a week with sandbags on either side of the head to prevent movement.

Also, patients were left with no replacement for the lens, which required them to wear coke-bottle glasses that distorted peripheral vision.

Intraocular Lenses

This serendipitous moment made Dr. Ridley remember a WWII fighter pilot who’d gotten plexiglass in his eyes after enemy bullets shattered his plane’s canopy. The plexiglass had been inert inside the eyes.

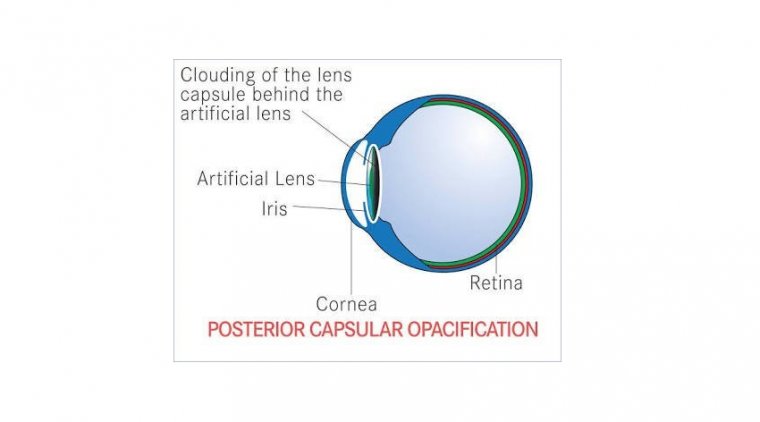

This observation led Dr. Ridley to develop and implant the first artificial lens in an eye after cataract surgery in 1949. Dr. Ridley eventually had success with artificial lenses, and word got out among his peers.

However, many colleagues considered his work to be malpractice or reckless — surgery at the time focused on removing things from the eye, not putting something in the eye. This hostility toward his work led Dr. Ridley to fall into depression.

“You can imagine what it must have felt like to have this idea you’ve spent your entire career perfecting, but people think you’re crazy. He would go to meetings and people would shout at him, or get up and leave, or tell him to go home. It was humiliating, it was embarrassing, and a lot of people would have given up.”

An ironic silver lining: in 1989 and 1990, Dr. Ridley underwent cataract extraction and IOL implantation, the standard of care, which helped him attain 20/20 vision.

Phacoemulsification

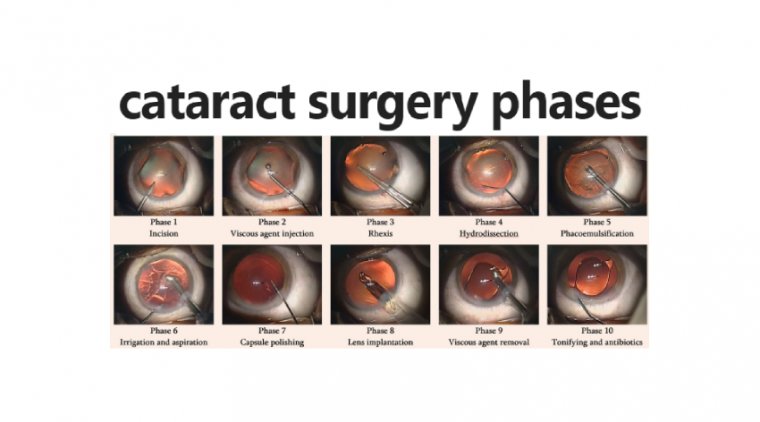

Charles Kelman improved on the previously large incisions and long recovery time by inventing phacoemulsification. He developed an ultrasonic probe to emulsify, or break up, the cataract into tiny pieces.

Dr. Kelman’s invention made possible today’s small incision, sutureless cataract surgery. He had persistence and belief in himself, but it wasn’t without costs.

Like Dr. Ridley, Dr. Kelman’s work was ridiculed by his peers, and his family life suffered. He and his wife divorced, partly because he spent so much time in the lab and away from his family. Dr. Kelman sacrificed much because he believed so strongly in his work.

Very few inventors or doctors in history have had as significant an impact on humanity. Everyone needs cataract surgery eventually if you live long enough. We’re all going to get phacoemulsification, as well as an artificial lens, so the impact is staggering when we think about the numbers.

Modern Cataract Surgery

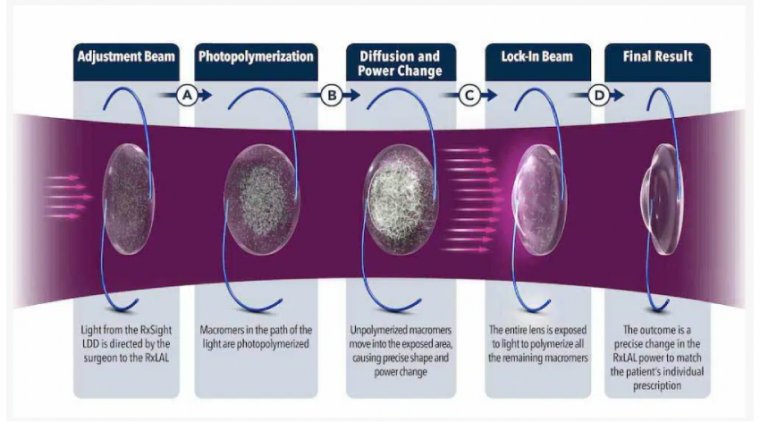

A recent development for cataract surgery is the use of the femtosecond laser. This is a great example of the future as it further improves on the procedure by increasing the odds of producing an excellent outcome.

Making an opening in the lens capsule requires manual dexterity and experience, and using a Femto laser eliminates that. “You line it up, activate the laser, and there’s a perfect circle. It becomes more automated and less prone to user error.”

Cataract surgery has come a long way since the days of impaling a lens with a long needle. While it may be easy to look at modern cataract surgery now and assume the procedure is perfected, the work of Drs. Kelman and Ridley have inspired ophthalmologists to constantly search for new ideas to better assist patients.

These men sacrificed and endured a lot and ultimately made the most significant advancements in ophthalmology. Their legacy is that we are now a field that is very open to new ideas and innovation.