Cataract Surgery – Glaucoma & Combining Laser With MIGS

The glaucoma surgical landscape has significantly changed in recent years. The conventional treatment paradigm began with hypotensive drops, laser surgery and traditional filtering surgery such as tube shunts and trabeculectomies.

Surgical practice patterns now reflect an increase in microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) as an option for glaucoma management. MIGS is an alternative to traditional glaucoma surgeries predicated on less invasive, more physiologic and less risky approaches to outflow enhancement.

As evidenced by the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial, nearly two thirds of patients initially present with early or moderate glaucoma.

As we move to a more interventional mindset for glaucoma care, mild to moderate disease may benefit from a less invasive procedure with modest intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering as this can aid in disease control, improve compliance or decrease eyedrop load.

MIGS aims to bypass the main area of conventional outflow resistance, the trabecular meshwork (TM), through stenting, dilating or cutting procedures.

Aqueous humor travels through Schlemm’s canal, traverses the TM and then drains through collector channels followed by aqueous veins and finally, episcleral veins to eventually enter the general circulation.

Most aqueous veins are found in the inferior quadrants (more so in the infero-nasal quadrant), and there are generally two to three of these veins in a normal eye. Aqueous humor flow is believed to be controlled by a pump-like mechanism.

The cardiac pulse, blinking and eye movements are thought to be the driving forces for transient oscillations in the collector system.

MIGS allows surgeons to tap into this mechanism and thereby treat the main area of resistance to outflow.

Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is the most significant risk factor for developing glaucoma and the only known risk factor that is currently treatable. In patients who already have glaucoma, reducing IOP slows the progression of the disease.

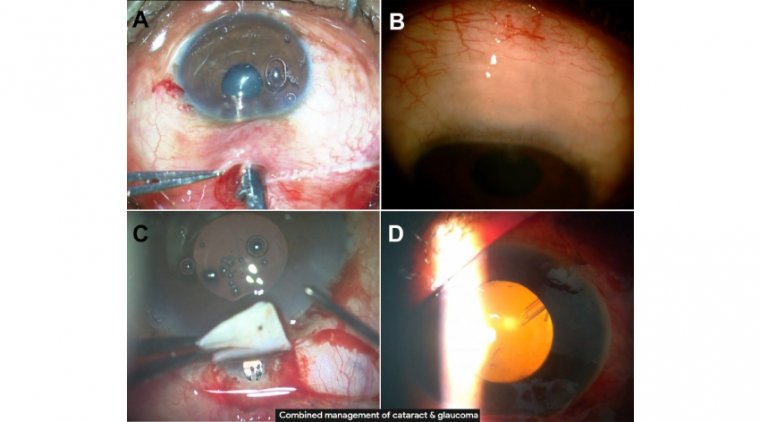

When patients come in with early to moderate glaucoma, we combine laser with several minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS). In over 90% of cases, we perform MicroPulse cyclophotocoagulation (CPC) as well as a canaloplasty and a trabecular meshwork (TM) bypass.

Our Approach

In our experience, the effect of the combination is additive. We use either iStent (Glaukos) or Hydrus (Ivantis) to allow aqueous fluid to bypass the TM and flow out.

The canaloplasty, using the Omni Surgical System (Sight Sciences), dilates Schlemm canal and the collector channels to enhance the natural outflow system.

The combination of TM bypass stents and canaloplasty with cataract extraction has been shown to be more effective at lowering IOP than the TM bypass alone with cataract extraction. We also do CPC procedures, and there are a lot of misconceptions about these treatments.

Some think of CPC as an aggressive, end-stage procedure that can cause signifi cant adverse effects and inflammation. A decade ago, CPC was seen as a last resort. Now that you do not have to use as much power, the procedure creates much less inflammation and the eff ect appears to be quite robust.

We have not had issues with hypotony, and inflammation has only been an issue in very limited cases, such as a patient with uveitic glaucoma, and these cases were able to be controlled with topical steroids.

In more advanced glaucoma cases, when we are targeting a bigger reduction in IOP, we use the Cyclo G6 Laser (Iridex) with the continuous wave G-Probe delivery device (Iridex).

The continuous wave laser energy is absorbed by melanin in the ciliary processes, and coagulative necrosis of the ciliary body reduces aqueous production.

We have found the process to be effective and repeatable, but it involves tissue ablation and there can be more inflammation than with the MicroPulse CPC.

More commonly, for mild to moderate glaucoma, we use the MicroPulse P3 delivery device with the Cyclo G6 Laser to perform transscleral laser therapy (TLT).

MicroPulse technology divides the laser beam into microsecond bursts that are interspersed with longer resting intervals. This allows the tissue to cool between pulses and reduces thermal buildup within the tissue targeted by the laser.

MicroPulse lasers do not cause thermal necrosis. Instead, they create a stress response that induces a biological effect. In our opinion, MicroPulse TLT is an underutilized nonincisional treatment, although its use is increasing.

Iridex reports that 180,000 patients have been treated with MicroPulse TLT in 80 countries. We have started using the procedure more often and earlier in the overall IOP reduction process.

MicroPulse TLT is 60% to 80% successful at lowering IOP by at least 20%. For MicroPulse TLT treatment, we have increased my power setting from 2000 mW to 2500 mW and slowed the speed of the 3 sweeps we do across each hemisphere to deliver more power to the tissues.

This is a manufacturer recommendation, and we find it to be more effective. Using the recommended 31.3% duty cycle, we now treat each hemisphere for 60 to 80 seconds by doing 3 sweeps of 20 to 25 seconds each.

We avoid about 30 degrees at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock position because there are long ciliary nerves there. I am now using the revised MicroPulse P3 Probe. It is a little thinner and it is easier to position, especially in patients with deep set eyes.

It has 2 plastic pieces—which look a little like bunny ears—that are placed on the limbus and help with alignment. It is very straightforward and quick.

We prefer to operate in an ambulatory surgery center, and we do the CPC laser in the preoperative area, after the patient has received a peribulbar block, while the operating room is being prepared.

This has created a very efficient flow for us. After the cataract extraction and the other MIGS treatments, the postoperative procedure is identical to my usual cataract postoperative regimen, which is generally an intracameral steroid and antibiotic and a nonsteroidal anti-infl ammatory drop for one month.

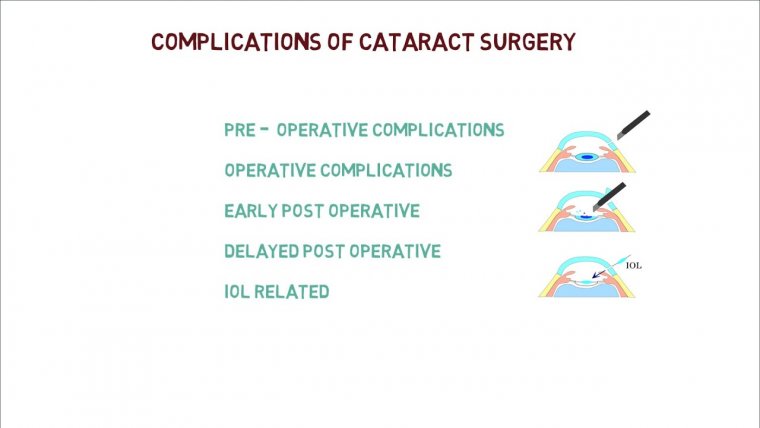

Slightly fewer than 5% of patients develop cystoid macular edema (CME). This includes all patients, even those with epiretinal membrane and diabetes, so the rate of CME doesn’t seem to be any diff erent than the standard cataract populations in my hands.

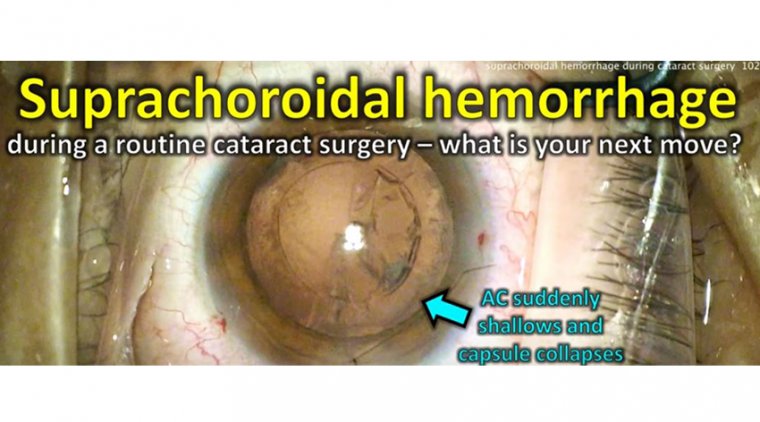

There is a less than 10% risk of postoperative hyphema with canaloplasty and trabecular bypass shunts. One tip when doing shunts and stents is to leave the pressure somewhat higher at the end of surgery.

It will reduce reflux into the anterior chamber. Now that we do this, targeting a maximum pressure of 25 mm Hg, our hyphema rate is probably between 2% and 4%.

After we perform the procedures, follow-up consultations are carried out by the patient’s referring doctor, which is sometimes hours away from my practice.

This makes it especially important for us to use procedures that will not cause pressure spikes or leave the patient’s eyes inflamed. Along with sending back patients who have quiet, unproblematic eyes, successful co-management requires communication and education.

Before the procedure, the referring doctor should know you do CPC laser and MIGS procedures. They can then begin prepping the patients, both through discussions and by initiating medication for patients with mild to moderate glaucoma, as insurance companies require patients be on medication before they have a trabecular bypass stent procedure.

While patients are having cataract surgery, we are really doing them a service if we also address glaucoma, which is a long-term threat to their vision.

We support being proactive and using all 3 procedures together. In my experience, this has been very safe and effective, and over 60% of patients are off drops and at target IOP.